|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

Wholly Hopkins Matters of note from around Johns Hopkins

In 1962, an accountant from Steubenville, Ohio, named George

H. Thompson began collecting the writings of H. L.Mencken,

the acerbic social critic and Baltimore newspaper columnist

who cast a jaundiced eye on American society during the first

half of the 20th century. Thompson began by acquiring a few

books here, some pamphlets there, then a few more books. By

the time he died in 2006, he had assembled a trove of nearly

6,000 items that leading Mencken scholar Richard J. Schrader

has called the greatest private collection in existence. |

|

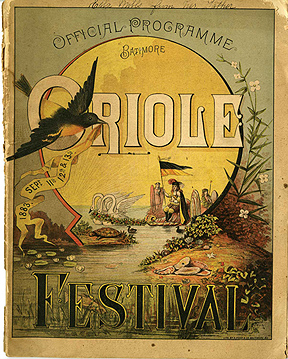

| A poster from the 1880s, promoting Baltimore's Oriole Festival. In his memoir Better Days, H.L. Mencken recalled the Oriole Festival parade as his first childhood memory. That prompted George H. Thompson to acquire the poster for his remarkable collection of Menckeniana. |

It now resides at Johns Hopkins. In August, the Sheridan Libraries

announced that the university had acquired the entire

collection, partly through purchase and partly through a gift

by the Thompson family. The books, magazines, and other items

will be cataloged and stored at the

George Peabody

Library, which already has the Robert A. Wilson

Collection of Mencken's works. Says Schrader, an English

professor at Boston College, "By adding this to the Wilson,

Hopkins now has a Mencken collection second only to [that of]

the [Enoch] Pratt [Free Library], which has the Mencken

archives. In terms of books, Hopkins clearly rivals the Pratt

and they're the better of anyone else."

It now resides at Johns Hopkins. In August, the Sheridan Libraries

announced that the university had acquired the entire

collection, partly through purchase and partly through a gift

by the Thompson family. The books, magazines, and other items

will be cataloged and stored at the

George Peabody

Library, which already has the Robert A. Wilson

Collection of Mencken's works. Says Schrader, an English

professor at Boston College, "By adding this to the Wilson,

Hopkins now has a Mencken collection second only to [that of]

the [Enoch] Pratt [Free Library], which has the Mencken

archives. In terms of books, Hopkins clearly rivals the Pratt

and they're the better of anyone else."Thompson was an astonishingly thorough collector. Schrader says of him, "Though not a scholar by profession, he made himself one. He knew things that hadn't been written down yet [by professional Mencken scholars]." Among the roughly 3,300 books are not just all the various editions of Mencken's work. There is also, for example, a volume about the Russian revolutionary Maxim Gorky's 1906 trip to the United States; because the book's appendix quotes a single paragraph from a letter written by Mencken, Thompson added it to the collection. He amassed the complete 15-year run of Mencken's magazine The Smart Set but also added any periodical that so much as published a photograph of Mencken. In the collection are letters, T-shirts that quote Mencken, and audio recordings not only of him but of events where he was discussed. Cynthia Requardt, the Sheridan Libraries' curator of special collections, believes the 2,000 magazines are the heart of the collection. Many of them are rare and hard to preserve; Schrader says that Thompson was a careful conservator, so that most of the collection is in superb condition. Even a brief look through the cartons of periodicals reveals that Mencken wrote for just about anybody. His work appeared in every leading magazine, as well as The Smart Set, of course, and The American Mercury, which Mencken founded with George Jean Nathan. But he also published articles in a woman's periodical called The Delineator ("A Journal of Fashion, Culture, and Fine Arts") and appeared in Gent, a journal of . . . well, actually, a mid-20th-century girlie magazine that billed itself as "An Approach to Relaxation." Sheridan librarians are in the process of opening boxes, indexing their contents, and placing items in the Mencken alcove of the George Peabody Library, which already holds the Wilson Collection. Requardt says the target date for completion of the cataloging is the next Mencken Day in September 2008. —Dale Keiger

Lisa Cooper, SPH '93, got some great news late last

September-the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

had named her one of its 2007 MacArthur Fellows. The

fellowships recognize extraordinary, creative individuals in

art, science, and public affairs with grants of $500,000 paid

out over five years. Cooper, a professor in the Johns

Hopkins School of Medicine, was cited for her landmark

work in helping to overcome racial and ethnic disparities in

health care. |

| Lisa Cooper |

Born in Liberia, Cooper is the first woman of African birth

ever to be named full professor in the School of Medicine.

She began as an instructor in the Department

of Medicine in 1994. Her first research found evidence

that cultural and social factors exert strong influence on

whether a person suffering from depression seeks medical

help, and where. Her subsequent work found that ethnic

minorities harbored greater fears of addiction to

anti-depressant medications; that African Americans regard

spirituality as significant in the treatment of depression;

and that, compared to whites, African Americans are more

likely to be suspicious of physicians and hospitals and ask

fewer questions of doctors.

Born in Liberia, Cooper is the first woman of African birth

ever to be named full professor in the School of Medicine.

She began as an instructor in the Department

of Medicine in 1994. Her first research found evidence

that cultural and social factors exert strong influence on

whether a person suffering from depression seeks medical

help, and where. Her subsequent work found that ethnic

minorities harbored greater fears of addiction to

anti-depressant medications; that African Americans regard

spirituality as significant in the treatment of depression;

and that, compared to whites, African Americans are more

likely to be suspicious of physicians and hospitals and ask

fewer questions of doctors.Cooper's current projects are a pair of trials. One is studying whether better communication skills among doctors and patients affect the patients' adherence to treatment for hypertension. The other is examining what happens when physicians and caregivers are taught how to deliver care that is culturally tailored to African Americans suffering from depression. She says she plans to apply her $500,000 MacArthur grant to extend the focus of her work to more people living in disadvantaged communities around the world. —DK

The boxes have been accumulating for 115 years, ever since

The Baltimore Afro-American weekly newspaper was

founded in 1892 by a former slave, John Murphy Sr. There are

now more than 2,000 cartons stashed in the back rooms of its

offices on N. Charles Street. Scholars do not know what might

be in those cartons because the archive has never been

indexed. |

| A World War II-era photo from The Baltimore Afro- American |

Beginning next January, that situation will be remedied. The

Andrew W. Mellon Foundation recently granted $476,000 to

Johns Hopkins to collaborate with Morgan State University and

the newspaper to sort the Afro-American's trove and

make its contents available to the general public. Faculty,

archivists, librarians, and students will comb through the

boxes and assemble an online database of descriptive tags,

called finding aids, that will permit scholars to efficiently

search the archive. The grant will support training of

Hopkins and Morgan State students in archival methods. Ben

Vinson, director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Africana

Studies, and Winston Tabb, the Sheridan Dean of University Libraries

at Hopkins, are excited about the opportunity for learning

that it will offer students. "This is a new kind of teaching

model that involves students from multiple classrooms and

multiple universities in a new kind of detective work,"

Vinson says.

Beginning next January, that situation will be remedied. The

Andrew W. Mellon Foundation recently granted $476,000 to

Johns Hopkins to collaborate with Morgan State University and

the newspaper to sort the Afro-American's trove and

make its contents available to the general public. Faculty,

archivists, librarians, and students will comb through the

boxes and assemble an online database of descriptive tags,

called finding aids, that will permit scholars to efficiently

search the archive. The grant will support training of

Hopkins and Morgan State students in archival methods. Ben

Vinson, director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Africana

Studies, and Winston Tabb, the Sheridan Dean of University Libraries

at Hopkins, are excited about the opportunity for learning

that it will offer students. "This is a new kind of teaching

model that involves students from multiple classrooms and

multiple universities in a new kind of detective work,"

Vinson says.Digging through the boxes has already produced the manuscript of an otherwise unpublished Langston Hughes play that apparently appeared in the Afro-American in the 1930s, as well as letters written by Hughes in the 1920s. "And those are just the tip of the iceberg," says publisher Jake Oliver, the great-grandson of the paper's founder. The Afro-American published work by notable black journalists and intellectuals such as Hughes, William Worthy, and J. Saunder Redding. More famous names appear in the visitor sign-in books, including Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Martin Luther King Jr., Billie Holiday, and Thurgood Marshall. Afro-American archivist Marilyn Benaderet believes the archive's true treasure lies in its record of daily life. "You can look at the photographs throughout the years and you'll be able to tell a lot about African Americans in those specific periods," she says. "You don't have a lot of that in African American history before the civil rights era." Tabb hesitates to predict when the project might be completed. The Mellon grant extends for three years, but Tabb says the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences and Sheridan Libraries will continue to support the project beyond that period. —Robert White

Since the fifth grade, Nikeeta Khetan's life plan has looked

something like this: Graduate from college, head straight to

Harvard Law School, embark on a career as a lawyer. But now

that she's a Johns Hopkins senior, double majoring in economics and political science, Khetan has rethought

that plan. Instead of starting law school in the fall, she's

decided to work in either banking or consulting. She hopes to

accept a job offer by Thanksgiving and join the workforce in

July. "I need more time on my own away from school before I

make the three-year, $150,000 commitment to law school," says

Khetan. |

|

Illustration by William L. Brown |

The decision to work right after graduation instead of going

to graduate school has become more common for Hopkins

undergraduates. According to an annual survey by the Johns Hopkins Career

Center, 47 percent of the Class of 2006 was working full

time six months after graduation, compared to 42 percent of

the Class of 2004. Only 38 percent of the Class of 2006 was

enrolled in a graduate or professional school after

graduation, compared to 41 percent in 2004. There are no

figures prior to that year.

The decision to work right after graduation instead of going

to graduate school has become more common for Hopkins

undergraduates. According to an annual survey by the Johns Hopkins Career

Center, 47 percent of the Class of 2006 was working full

time six months after graduation, compared to 42 percent of

the Class of 2004. Only 38 percent of the Class of 2006 was

enrolled in a graduate or professional school after

graduation, compared to 41 percent in 2004. There are no

figures prior to that year.Mark Presnell, director of the center, which serves students from the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences and the Whiting School of Engineering, points to the healthy economy as one reason for the increase in Hopkins students seeking jobs after college. Another factor, he suspects, is the Whiting School's current greater emphasis on industry jobs as opposed to academic research. Then there's the growing presence of humanities majors among Krieger School undergraduates. They get a good general background in research, analysis, and problem solving as liberal arts majors, then look for jobs to which they can apply these skills, Presnell says. Between 2005 and 2006, the annual number of appointments students made with career counselors increased by 58 percent, from 1,131 to 1,786. And the number of employers participating in on-campus career fairs has grown by about 25 percent in the last few years. "This year for the first time we closed the Fall Career Fair to employers because we don't have any more room," Presnell says, noting that 105 companies were scheduled to participate. To accommodate the growing number of job-seeking graduates, Presnell has added two staff members to the Career Center's office, increased the number of employers who recruit on campus by 35 percent to 334, and changed the center's Web site to better teach students about finding internships and jobs. In addition, his staff reaches out to freshmen and sophomores about how to get internships and gain valuable work experience outside the classroom. "We're definitely more active in the Hopkins community, especially with younger students," Presnell says. "Now it's no longer employers asking, 'Did you have an internship?' They want to know if you've had two or three." —Maria Blackburn

Hopkins builds a public library

Candida Singleton has long been a regular at the Orleans

Street branch of the Enoch Pratt Free Library. A couple of

times a month, Singleton walks the few blocks from her East

Baltimore house to the library with her son, Demond, so he

can check out books on sports and the solar system. "I want

him to read every day," she explains. |

| Photo ©Patrick Ross / Patrick Ross Photography |

Since August, the Singletons have walked to a new 15,000-square-foot building at the corner of Central Avenue and Orleans Street. As part of a land swap with the Enoch Pratt, Johns Hopkins Medicine acquired the public library's former site at Broadway and Orleans to build a pavilion for patients and their families. In exchange, Hopkins built a new $5.1 million library on a parcel of land donated by Baltimore. The new library is about the same size as the old building but has more meeting space and a design that's more open and inviting, says Michael Iati, director of architecture and planning for Johns Hopkins Hospital. "The building is not elaborate, but it's just such a nice, calm, elegant space," he says. "It looks like a space that you'd want to spend time in." Features include a children's story room, a teen area, 16 computer stations, and free wireless Internet access. The branch also houses the Pratt Center for Technology Training, where free computer classes are so popular there are waiting lists to enroll. The meeting room-which the old branch didn't have-is being used for community meetings and for library programs such as teen art classes and author visits. "Our meeting space is one of the most popular things here," says branch manager Virginia Fore. "[By early fall] we already had people asking for bookings in January." Located within walking distance of four schools, including Paul Laurence Dunbar High School and Sojourner-Douglass College, the branch has come to be thought of by Enoch Pratt executive director Carla D. Hayden as the library's education branch. Its use by area students of all ages has exceeded her expectations. She says, "We already knew that we were the on-ramp to the information superhighway, but this branch is really a shining example of that." —MB

In nursing, the push for professionalization has been a

constant. The latest evidence: The American Association of

Colleges of Nursing (AACN) has recommended that by 2015,

practitioners in advanced fields-clinical nurse specialists,

nurse anesthetists, nurse midwives, nurse

practitioners-should hold a doctor of nursing practice (DNP).

In response, the Johns

Hopkins School of Nursing has created a DNP program that

will enroll its first cohort of 25 students this January,

with a second class to begin studies next September. |

| Offering nurses the chance to practice at the highest level makes sense, says Phyllis Sharps. |

Given nurses' increasingly important role in health care,

offering them the chance to practice at the highest level

makes sense, says Phyllis Sharps, professor in Nursing's

Department of Community and Public Health and a member of the

task force that put the Hopkins program together. "It's

nursing moving toward being more consistent with the

preparation of the other allied health professions." The

degree, she says, will be in line with the MD that physicians

earn, or the PharmD for pharmacists.

Given nurses' increasingly important role in health care,

offering them the chance to practice at the highest level

makes sense, says Phyllis Sharps, professor in Nursing's

Department of Community and Public Health and a member of the

task force that put the Hopkins program together. "It's

nursing moving toward being more consistent with the

preparation of the other allied health professions." The

degree, she says, will be in line with the MD that physicians

earn, or the PharmD for pharmacists.Hopkins' new DNP came out of the recommendations of the AACN, the accrediting agency for four-year and higher nursing programs. A few years ago, the AACN advised that a practice-focused doctoral program-rather than a master's degree-should be the new standard for expert advanced practice nurses. Those practitioners currently certified with master's degrees will be grandfathered and not compelled to earn the new doctorate. The School of Nursing already offers a research-based PhD, but this new degree is different, focused on clinical practice for nurses in the field, such as nurse practitioners, and indirect practitioners such as nurse informaticians and health policy analysts. It is meant for working nurses who already hold master's degrees and will be offered as a combination of electronic and classroom interaction. Students will come to campus for two weeks of classes, and once more for a final presentation, each semester, with the rest of their work conducted online. The 38-credit degree is designed to be completed in four semesters, says Kathleen White, director of the current master's program and interim director of the DNP program. Also important for most nurses will be the $9,500-per-semester price tag, which falls within the reim-bursement limits of many of their employers. About 140 DNP programs already exist around the country, but most, like the one at Hopkins, are relatively new. Unlike some programs that focus narrowly on just nurse practitioners, White says, Hopkins' DNP will reach out to a broader spectrum. "We are going to stress the importance of leadership and interdisciplinary collaboration," she says. "We are going to include both direct and indirect practice, and that will also distinguish us." The eight faculty members on Hopkins' DNP working group meet once or twice a week to hash out course descriptions, curriculum, and other details. White is excited for the first 25 students who will take their place in the program. "It should be a rich cohort," she says. —Kristen A. Graham

In the mid-1970s, Nobel laureate Linus Pauling and Scottish surgeon Ewan Cameron reported a startling finding: Advanced-cancer patients treated with megadoses of vitamin C survived significantly longer than patients not so treated. Vitamin C therapy was a controversial idea. Many researchers dismissed it, asserting that Pauling's study had been flawed. At the end of the decade, the Mayo Clinic conducted large-scale trials, testing vitamin C on a number of cancers. The trials found no consistent benefit to Pauling's therapy.

Dang and his team were trying to learn how the Myc oncogene, prevalent in at least 25 percent of cancers, triggers tumor growth. They knew that when activated, Myc produces highly reactive molecules called oxygen free radicals. The prevalent belief was that these free radicals damage DNA, which leads to cancer. According to this idea, if an antioxidant like vitamin C worked, it was by preventing free radicals from doing damage. In their study, Dang and his colleagues implanted mice with human lymphoma and prostate cancer cells and activated Myc, which produced free radicals. Then they gave the mice water spiked with one of two antioxidants, including vitamin C, to destroy the free radicals and thereby prevent DNA damage. After a few weeks, the researchers found that the tumors implanted in the treated mice had not grown. The antioxidants apparently had worked. But not as expected. The control mice, not given antioxidants, showed tumor growth and an abundance of free radicals-but not DNA damage. The researchers realized that if tumors grow despite the presence of free radicals and undamaged DNA, then, in the test mice, it wasn't the destruction of free radicals that halted the tumor growth. The antioxidants had to be working some other way. "That was a surprise," says Dang. He and postdoctoral fellow Ping Gao, lead author on the paper, thought the answer might lie with a protein. Malignant tumors often deplete the oxygen in their vicinity, which would inhibit their ability to convert sugar into energy were it not for HIF-1, a protein that enables energy conversion without oxygen. The flourishing cancer cells in the untreated control mice had an abundance of HIF-1. The treated mice did not. HIF-1 levels depend on the presence of free radicals. The researchers hypothesized that destroying free radicals by applying antioxidants worked because it lowered HIF-1 levels, eliminating the cancer's back-up energy source. To test their hypothesis, they repeated their experiment with a mutant form of HIF-1 that is not dependent on free radicals. In that test, the cancer cells survived the antioxidants. If more animal research confirms the findings, Dang hopes to design a human clinical trial around antioxidants. In the meantime, he cautions that there is still no hard clinical evidence that vitamin C cures cancer in people. "You can't keep smoking your two packs of cigarettes a day and just start taking vitamin C," he says. —Kristi Birch

Ralph A. Alpher, a former

Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) physicist

considered the "lost father" of the Big Bang theory, died on

August 12 in Austin, Texas. He was 86. |

| Ralph A. Alpher |

Along with his adviser, the Russian-born physicist George A.

Gamow, Alpher today is widely recognized for pioneering work

on a formula to calculate the abundance of elements left

after the explosive creation of the universe 14 billion years

ago. Alpher posited an initial matter, which he dubbed "ylem"

(Greek for "primordial elements of life"), that decayed after

the Big Bang. As the infant universe cooled, the particles

left from this decay-protons, neutrons, and

electrons-combined to form all the known elements. In 1948,

The Physical Review published Alpher and Gamow's

findings, which were based on Alpher's doctoral dissertation

at George Washington University.

Along with his adviser, the Russian-born physicist George A.

Gamow, Alpher today is widely recognized for pioneering work

on a formula to calculate the abundance of elements left

after the explosive creation of the universe 14 billion years

ago. Alpher posited an initial matter, which he dubbed "ylem"

(Greek for "primordial elements of life"), that decayed after

the Big Bang. As the infant universe cooled, the particles

left from this decay-protons, neutrons, and

electrons-combined to form all the known elements. In 1948,

The Physical Review published Alpher and Gamow's

findings, which were based on Alpher's doctoral dissertation

at George Washington University.Several months later, Alpher and APL physicist Robert Hermann published a paper that said there must be remnants of the Big Bang still echoing in space as background radiation. There was no confirmation of their theory until 1964, when Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson of Bell Telephone Laboratories, using a powerful radio astronomy antenna, stumbled upon traces of the radiation that Alpher and Hermann had predicted. The discovery received wide acclaim and in 1978 earned a Nobel Prize for Penzias and Wilson. Alpher's contribution went mostly unacknowledged. Alpher's theory later paved the way for physicists John Mather and George Smoot, who, with the aid of NASA's Cosmic Background Explorer satellite, found temperature fluctuations in cosmic microwave background radiation. The discovery further bolstered the Big Bang theory. Mather and Smoot shared a Nobel Prize in 2006. Alpher would later be recognized by several physicists who sought to give him overdue credit for his work. The professor emeritus of Union College attempted to set the record straight himself with his book, co-authored by Hermann, Genesis of the Big Bang (Oxford University Press, 2001). Two weeks before his death, Alpher finally received high honors when he was awarded the National Medal of Science. Due to Alpher's failing health, his son accepted the award on his behalf in a July 27 White House ceremony. John C. Sommerer, director of science and technology and chief technology officer at APL, says that although unheralded for most of his life, Alpher's contributions to physics and the field of cosmology are considerable. "He made the inference that the expansion of the universe began suddenly, and that that beginning left a relic still detectable. That is huge," Sommerer says. "He basically laid the groundwork for discoveries that would later be worth four Nobel Prizes. Not bad. Unfortunately, he was awarded none." —Greg Rienzi

In the cult TV show The 4400, characters ponder use of

a fictional drug called promicin. Take it, and there's a 50

percent chance you will develop a supernatural ability like,

say, telekinesis. The catch? Fifty percent who inject

themselves with the neon-green liquid suffer a painful

death. |

|

Illustration by Robert Neubecker |

That's an absolute benefit-and-risk equation that Edward J.

Bouwer can appreciate. If only more health choices were so

black and white. In his new book, The Illusion of

Certainty: Health Benefits and Risks (Springer, 2007),

Bouwer, chairman of the Whiting School's Department of

Geography and Environmental Engineering, and co-author

Erik Rifkin, president of an environmental consulting firm,

argue that too often the benefits of drugs, screening tests,

and elective surgeries are presented as certain. The truth

can be murkier.

That's an absolute benefit-and-risk equation that Edward J.

Bouwer can appreciate. If only more health choices were so

black and white. In his new book, The Illusion of

Certainty: Health Benefits and Risks (Springer, 2007),

Bouwer, chairman of the Whiting School's Department of

Geography and Environmental Engineering, and co-author

Erik Rifkin, president of an environmental consulting firm,

argue that too often the benefits of drugs, screening tests,

and elective surgeries are presented as certain. The truth

can be murkier."Unlike diseases caused by pathogens, with chronic diseases we often don't know the direct cause, just risk factors," Bouwer says. "All this uncertainty is brought into the picture." Uncertainty and misinformation, the book argues. Take cholesterol, to which Bouwer and Rifkin devote two chapters. Unless you've been watching too much cult TV, you've heard high cholesterol cited as the primary controllable risk factor associated with coronary heart disease (CHD). Nearly 20 million people worldwide take cholesterol-lowering medications such as Lipitor and Zocor. Television commercials claim that the risk of CHD becomes markedly lower when you use drugs to reduce your blood serum cholesterol levels. Bouwer and Rifkin take issue with terms such as "markedly," saying that high cholesterol is just one of many risk factors associated with heart disease, and that two large and reputable clinical studies found that nearly the same number of individuals with normal cholesterol acquire CHD. One significant problem arises from citing statistics for relative risk reduction instead of absolute risk reduction, say the authors. Drug companies, the media, even health professionals often use a relative risk reduction percentage to convey a benefit. But that can be misleading. For example, if only one out of 100 people gets liver cancer when using drug X, compared to two out of 100 not on the drug, drug X could be marketed as reducing the risk of liver cancer by 50 percent. But that's the relative number. The absolute risk reduction in this case would be only 1 percent. Try advertising that statistic. "How often do we hear things like, 'Eat chocolate and you have a 10 percent chance of such-and-such not happening'?" Bouwer says. "We are bombarded with relative risks, and we don't know how to put them into context, unless we have the absolute numbers." The public should give more weight, Bouwer says, to the latter figures. In addition to cholesterol, the book examines risks and benefits of screening tests for prostate and breast cancer, drinking chlorinated water, and using anti-inflammatory drugs such as Vioxx. The authors also look at the risks from smoking and exposure to environmental contaminants such as dioxin and radon. To demonstrate absolute health risks and benefits in a more vivid and immediately graspable manner, they developed a graphic-a 1,000-seat "Risk Charac-terization Theater" (RCT), complete with stage and seats. Using existing data, the authors darken seats to represent the number of people likely to benefit from a medication or be at risk from an environmental contaminant. One of the book's RCT graphics, for example, illustrates that if 1,000 people with elevated cholesterol levels (280 mg) were sitting in a theater, only one additional person out of this group would die from CHD, compared to the same number of those with normal cholesterol. In the case of colorectal cancer screening, the RCT shows that one colon cancer death would be avoided for every 1,000 people screened.vv Presented with clear and easy-to-read data, Bouwer says, people can make better-educated decisions. "In a lot of cases, the health benefits of a drug or test are overstated and the risks not made clear," says Bouwer. "When you use absolute risks, [the actual benefit] really shows up." Bouwer says he doesn't want people to stop listening to doctors or abstain from screenings or medications. Rather, he hopes a book like this will enable people to make more informed decisions and better assess health risks them-selves. "Science cannot tell you what is an acceptable risk," he says. "You have to decide for yourself." —GR

Imagine examples of rude behavior. Didn't take long, did it? Surveys indicate that most people believe uncivil behavior is on the increase, and they have no trouble compiling lists of bad manners. In 1997, P. M. Forni, professor in the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences' Department of German and Romance Languages and Literatures, co-founded the Johns Hopkins Civility Project (now the Civility Initiative) to promote study and discussion of manners in contemporary society.

Below is "The Terrible Ten," the survey's list of the worst behavior, according to the respondents, ranked by degree of offensiveness.

1. Discrimination in the workplace

The three riders of the health care apocalypse

"Consistency, complexity, and chronic illness: These are the

three riders of our health care apocalypse. These are the

three challenges we must confront. The presidential

candidates have been talking a lot about costs and insurance

coverage. But until we confront consistency, complexity, and

chronic illness, no effective cure for our ailing health care

system is feasible."

Advising the Iron Man on winning in business

Earlier this year, 28 MBA students from the Carey Business School lived

many a wide-eyed child's dream: They got to meet Cal Ripken

Jr., former Baltimore Orioles star and newly inducted member

of the Major League Baseball Hall of Fame. But the students

weren't asking for autographs; they were presenting their

research meant to help Ripken's company, Ripken Baseball

(RBI), achieve greater success. |

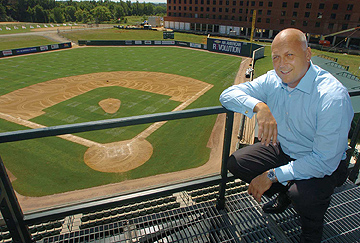

| Former Baltimore Orioles star Cal Ripkien Jr. wants his business to grow, with some help from Johns Hopkins. |

The students are the first cohort of the school's MBA Fellows program, a track that differs from traditional MBAs in its project-based approach. Typically, an MBA program consists almost entirely of coursework, with perhaps a single culminating project, called a capstone. But these MBA students eschew the quad and the classroom in favor of real-life learning: two years and nine projects with actual companies. Rick Milter, who directs the program, calls it "nothing but capstones." RBI, owned by Cal and his brother Bill (also a former major leaguer), operates two minor league baseball teams in Maryland, training academies for amateur athletes and coaches, a nonprofit foundation, and a sports management service. Milter and the Carey Business School faculty approached the company because it needed expert advice on improving its overall growth strategy, especially regarding geographical expansion-where best to locate a new academy or tournament destination? The cohort split into six teams, four of which concentrated on analyses of possible real estate opportunities. The students did case studies to determine the feasibility of locations according to criteria such as demographics, climate, and accessibility. The teams came back "with an unbelievable array of ideas," says Chris Flannery, RBI's chief operating officer. Some of those ideas had nothing to do with potential sites. MBA fellow Shirley Murry and her team designed a new educational initiative called the "Ripken Way." "The concept capitalized on Ripken's image and principles," she says. "We suggested that they implement a curriculum that includes education through sports, the Ripken values of keeping it simple, making it fun, and celebrating success." RBI has published the "Ripken Way" on its Web site and begun using it in its management training curriculum. Murry is now working on an individual project with the company, doing competitive and market analyses to help it open a facility in Southern California. According to Flannery, much of the students' work continues to have an impact on the company's future direction. "It's still alive today," he says, praising their efforts. —Simon Waxman, A&S '07

Compulsory love and obligatory fear

"[Religion] tells us that we could not arbitrate our most

essential integrity-the difference between right and wrong-if

we were not afraid of the celestial dictatorship. A

dictatorship that tracks us while we sleep, that can convict

us of thought-crimes because it knows what we're thinking

before we think it. This is the origin of totalitarianism-the

unending fear of someone whom you must fear and are ordered

to love, compulsory love and obligatory fear and no escape

and no freedom and no privacy." |

|

|

The Johns Hopkins Magazine |

901 S. Bond St. | Suite 540 |

Baltimore, MD 21231

The Johns Hopkins Magazine |

901 S. Bond St. | Suite 540 |

Baltimore, MD 21231Phone 443-287-9900 | Fax 443-287-9898 | E-mail jhmagazine@jhu.edu |

|