|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

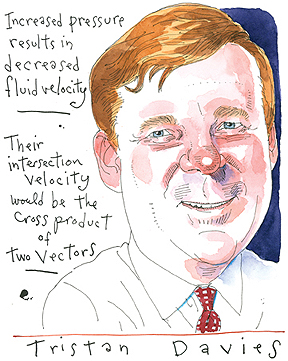

Short fiction by Writing Seminars faculty member Tristan Davies The only place to sleep on the night train from Hendaye was on the floor, in a corridor, head-to-toe. There were three of them: Evan, Soren, and Kurt, all engineering students at Johns Hopkins. They had been to Pamplona for San Fermín. "Bernoulli's law," Soren had said as they watched the running of the bulls from atop a stockade fence. "The bulls represent a concentration gradient," said Kurt. The first rocket sounded, propelling a rush of humans. "Like a submarine at great depth." "More like a bullet through the air," said Soren, "given the mass and velocity differential." "More like sex," said Evan. The sea of white and red separated for a knot of six large black bulls, their horns tossing, their hooves clattering on the pavement. The rest of the day passed in a bull-stew blur, punctuated by exclamations of spraying champagne. As they slept in their cramped line on the floor of the train, Evan dreamed of Megan Lukens. She was his girlfriend in Baltimore and she was a biomedical engineering student. They left their backpacks at their hotel in the Latin Quarter and ate grilled sandwiches in the rue de la Huchette. They drank wine in a crowded bar, then took a long walk. They slept the afternoon in the hotel, exhausted from the night spent on the filthy floor of an SNCF. A continual crowd passed in the street below. When they woke, they joined up with two Canadian women from their hotel and a Swiss man. They were going out to an inexpensive German place — liter steins of beer and French cigarettes. Evan watched blue smoke as it rose from between the fingers of one of the Canadian girls. At first it demonstrated perfect laminar flow until, its velocity decreasing, turbulence set in. She was a pretty girl wearing a service station attendant's pinstriped shirt, the name Bob in an oval of red embroidery on the right breast. She was older than he was, Evan guessed. If only by a year or two.

Because Evan would not sleep with many women in his life,

after his first child was born, he would often find himself

thinking of the women he might have slept with, but didn't.

There weren't a great number of them, either. Bob.

He didn't remember her actual name. |

|

| Intentional contact. They didn't speak. Bernoulli's law: Increased pressure results in decreased fluid velocity. Like the smoke from her cigarette, he thought, like a cigarette should. |

The group paid their bill carefully, the way traveling

students will. They wandered back toward the hotel. The

Cluny Museum. The narrow streets. The Canadian woman with

the station attendant's blouse lagged back with him.

Vectorial, he thought of the street: short straight

stretches, a few storefronts of painted glass and cast

iron, before the direction shifted, countervailed by some

ancient obstacle and redirected. They followed the external

angles. He and the Canadian had slowed to the point where

they were barely walking. They were at the middle of a long

block lined by tall and narrow townhouses, all four stories

tall, with mansard roofing, and dark. She brushed against

him. Intentional contact. They didn't speak. Bernoulli's

law: Increased pressure results in decreased fluid

velocity. Like the smoke from her cigarette, he thought,

like a cigarette should. He turned toward her.

Curl curl v, he calculated. Vorticity.

Navier-Stokes. Their intersection velocity would be

the cross product of two vectors. At that moment, he thought again of Megan Lukens. Megan was from Michigan. Her parents were both chemical engineers, from the Upper Peninsula. Yoopers, she called them. They wanted Megan to be an engineer, too. She was smart enough. Among Evan's friends, none of whom were dumb — Soren did programming year-round for a defense contractor and Kurt was as good at physics as he was at mechanical engineering — Megan was the smartest. When they were working through a problem set, she would sit by quietly. When they had exhausted their options, she would pull back her hair and blink her eyes and know the answer. But she was unhappy as a biomedical engineer. She wanted to draw. It was never an option for her to come to Europe. Her parents would not allow it. They were good Catholics and Yoopers and clung to the shallow roots they had set below the Mackinac Bridge. They weren't interested in their daughter traveling with a boyfriend, a half-Jewish atheist, drinking wine at lunch and visiting art museums. Running with the bulls. Doing all the touristy things. Instead, she remained in Baltimore and studied art history. The summer term was the only time she could. The cars were parked halfway up on the sidewalks. The street was that narrow. The shirt that the girl wore, he realized, was real — not some fake thing from the Gap or Abercrombie and Fitch. He could see that the pinstripes were broken blue, like the faint interlines on a child's writing tablet. She stood that close to him. The shirt had the real ghosts of real grease stains, turned yellow after frequent washing. Bob? It seemed too obvious, too obviously a trick of memory. An electric bell rang near them. Evan thought about this as he lay awake. His infant daughter, only three weeks old, slept in her bassinette at the foot of the bed. She made little noises when she was restless. Beeping, Evan called it. His wife slept, exhausted, beside him. She had had a difficult pregnancy and a complicated delivery. He looked at the clock. Two hours until the next feeding. The night concierge threw open the hotel door. Soren, Kurt, and the other Canadian had stirred her. She had no interest in rousing again from her hutch for stragglers. Evan and the Canadian woman paused on the pavement, startled from their moment. The concierge, a crude-looking woman in an apron, hissed at them in a faintly fascist and scabrous French. Still, as an engineer, Evan felt responsible to authority. They went in. Neither of Evan's parents were engineers. They didn't understand his interest in it.

The Canadian woman made her way through the fluorescent-lit

lobby. Was it the accent that ruined it for him? The faint

hint of Megan's, her accent being only faint itself? The

slight elongation of her vowels, particularly when she was

laughing. Megan said that her parents had erased their

Yooper accents. It was a point of pride. It was a part of

their studied struggle to come up in the world. However,

when they were angry or upset, her parents might slip back

into it. Megan could imitate the accent brilliantly. When

she spoke that way, they would both burst out in laughter.

What were the odds, because he didn't usually meet women

who were forward, that she'd be Canadian, with the accent?

He followed her up the curving staircase. She took out a

key and unlocked her door. Evan wished her goodnight. She

closed the door behind her without looking back. |

|

Evan slept poorly. Too much German beer. They had been

drinking a lot. Wine at lunch, every day. Nights out. Once

at breakfast seeing two men order eau de vie, Soren

had begun taking a shot with his morning coffee. Kurt

thought that Soren was developing a problem. Evan thought

that Kurt, short and stout, drank even more than Soren. He

got out of bed. The two others shared the double. The room

was hot and close. Kurt snored. Evan opened the French

windows. Somewhere in the hotel a women cried out in

passion. Her moans echoed off the building opposite in the

narrow street. Evan went out into the hall, down to the WC.

When he woke again, civil-twilight blue in the open window and the smell of bread in the air, he thought more of Megan. He rose, pulled on a pair of jeans, and walked again down the quiet hall to the WC. He washed in the bidet, the way he'd seen a girl clean herself in a hostel outside Barcelona. Their next "rendezvous," as they called them in their geeky and engineering way, was in the Richelieu Passage of the Louvre. A group of Hopkins students were on a language course. They were rising sophomores and mostly girls. Soren and Kurt were interested in meeting the girls. They thought they'd have more chance with Hopkins girls in France. They thought they'd have more chance with girls in France if they were from Hopkins. Evan was curious about the group leader, a French teacher called Evie Lloyd. The entire group stood on line, looking pitiably American. Soren, who was practically Swedish, and Kurt, who looked Indian though he wasn't, had begun taking pride in being mistaken for Europeans. With this group, however, there was no chance. Nevertheless, they were mostly female. They went to work. Neither Kurt nor Soren was particularly successful with the other sex; but the Hopkins girls, distant and suspicious, were like curry to an itinerant Hindu. The line moved forward. Evan stayed near Evie. He knew her through Megan, who, with a score of five on her German A.P., took French. Megan and Evie became friends. They had lunch together on odd Fridays and went shopping. Once Megan took Evan to Evie's house for drinks. She lived in an expensive neighborhood up the JFX. They sat on a deck and drank wine, admiring a yard that was a rhubarb of Baltimore spring: fading daffodils and bright, early tulips; the first of the dogwoods; redbud trees aflame. The lawn, an impossible emerald color, was littered with the pink cat's paws of magnolia blossoms, which had blown over from a neighbor's magnificent tree. On the drive back to Homewood, the banks of the Jones Falls were tumultuous with hardwood climax blossom. Evan thought that tonight Megan might finally sleep with him. "What's the worst thing that could happen?" he asked, a little drunk, which was the only way he could talk about it. "I will take care." "How about eternal damnation?" Megan asked. "Do you have protection against that?" Evie and Evan talked. The next he knew he stood beside her on the Samothrace Landing. Evie, though certainly twice Megan's age, was nearly as thin as Megan and just as tall. He couldn't help making the comparison. And the contrast: She had a child now in private school. She signed grade cards at Hopkins. She was teaching a course in Paris. Again, he felt his pace slowing. A Venturi effect: A vacuum expanded above them, a vast dome into which they might rise. "I don't care," said Evie. "Sculpture. Painting. French. Dutch. Raft of the Medusa? Don't say Mona Lisa." Kurt and Soren disappeared with the group. It came time for lunch. Evie took his hand. "Hurry," she whispered. They were out on the rue de Rivoli. Before he knew it, they were already a block away from the museum, rushing, nearly running, viscous flow, through the tourist crowds, past an arcade, down an alleyway, into a courtyard, up the steps of a small restaurant. Without fully understanding how it had all come about, a jar of gherkins, accompanied by a pot of mustard, sat before him. They ate and they drank wine. "One of the girls, the French girls, has a crush on you," Evie told him at the end of the afternoon. "Is that all?" Evan asked. "I think you know what I mean." Evan and his two friends were invited to the French girl's house for dinner. The next day, the three of them rode to the suburbs on the afternoon commuter. Evie and the girl in question, who Evan hardly recognized — small, young, and very dark — met them on the platform. They strolled up a short hill through the afternoon light to her parents' house: a blue metal door in a wall. They weren't wealthy people; the father worked for SNCF. The Hopkins girl being hosted by the French family hadn't made the walk to the station. None of them, dressing earlier, had been able to remember which she was. They remembered, though, when they saw her: pale, kinky red hair, angry. She was uninterested in seeing three Americans and completely embarrassed to have them in her "home." She told them as much as they stood just inside the living room, overwhelmed by the smallness and the smells of cooking. "Don't worry about her," Evie whispered in Evan's ear. "And be nice to her," she said, nodding to the small French girl. "Two French girls who want you. You're quite the lover." An aunt and uncle arrived with a cousin, followed by someone Evan took to be a neighbor. They sat, the 12 of them, at the family table, expanded to its fullest length and set with sincere elaboration. Soup. The three Americans gorged. Next came an entire poached fish. They ate heartily. A leg of lamb. A second dinner! A sorbet? Odd dessert, considering. A large, roasted guinea hen came. Even Kurt, who frequented Chinese all-you-can-eat buffets during the school year, looked nervously toward Evie. A salad next, accompanied by fruit and nuts. Reprieve. Then cheeses, too many of them — each one with a story, each one to be tried. Soren looked green. Evan hadn't eaten since taking a polite bite of guinea hen. Champagne! Toasts! And, finally, a gigantic baked Alaska (or some French province, Evan supposed) in special honor of the esteemed visiting guests. As he lay in his bed, wife beside, baby at the foot in her bassinet, Evan carefully went through the chronology of it. The Canadian was on Friday. No: Thursday. The museum was Friday. The dinner the next evening. The French ate so much food. With Evie at lunch he had eaten: the gherkins, then mixed salamis, followed by ravioli stuffed with lobster meat. Cheese. A dessert. The French ate so much fish. Why? Never in his life had Evan eaten the way he had at those meals. To this day, he drank milk with his dinner. But he could remember every course. He could remember the taste of the gherkins snapping in his mouth as he felt Evie's sandaled foot brushing against his calf beneath the table. His wife started, opening an eye. Evan did not move. He didn't want to wake her fully. The baby beeped. Ninety minutes to her next feeding. His wife rolled to her opposite side, her shoulder sharp beneath the clothing, her back to him. His exhausted wife. He would work tomorrow. Somehow he managed. It reminded him of grad school. It reminded him of Hopkins. The next morning, Evie dictated Evan's bread-and-butter note. They were at an outdoor café, drinking coffee and mineral water. He followed her instructions. He might as well have been writing Chinese, with all the acutes and the graves, the cedillas and the circumflexes. Evie was not impatient; neither was she sympathetic. Evan signed his name, folded the letter, stuffed it into a French envelope, and licked the flap. He copied the Bergenoirs' address from a set of folded papers, fraying and written over in colored pen, taken from Evie's bag. Evie had French stamps in her wallet. They carried the envelope to a postbox. Evan dropped it in and then Evie kissed him, there on the street, people passing by. They kissed some more leaning against the yellow box. Kurt was married now, too. He was still in Maryland as well. Rockville. He called faithfully twice a year. Each December brought the novelty of a photo Christmas card: two strange new people in sweaters, posed before a cardboard reindeer, white cotton wool glued everywhere, their small faces covered with hints of recent tears. Soren, in contrast, had disappeared shortly after graduation. Too smart, too intense, too confused. The last Kurt saw of him was over coffee at an IHOP in Wilmington. Soren complained about "savage howling nature outside the window." Kurt took it personally. He was proud of keeping his network of Hopkins guys together. He went to all their weddings. He hung out with them in Vail and Phoenix when they first started getting divorced. Kurt was in pharma. He traveled a lot. Evie told him to meet her by the Seine. Neither Kurt nor Soren wanted to come along. They hadn't enjoyed any luck with the girls on Evie's trip. Now lying stretched across the beds of the increasingly small and tiresome dormitory room, Kurt and Soren complained that the Hopkins girls were all too uptight or unattractive or hung-up on their boyfriends back home. Evan wasn't so sure. What about the pretty, slim girl called Cindy, who wore a dangling earring from her navel? What about Becky, the girl with the alluring smile and the hip glasses? And Rachel? Tall, Chinese, and pretty: Didn't she always gravitate their way? In his newfound suavity, Evan had begun to see responsive women everywhere. In a stationery shop, the salesgirl lingered over the wrapping of a disposable pen. At a flower kiosk on the rue de Bac, a dark, barefooted girl paused from her arrangement and smiled. Was it his well-worn khakis? His wrinkled shirts? The inattention that he now paid to his hair? Before he'd always been so careful about his appearance. As he caught sight of himself, thin, tanned, tussled, in a window on the street, he wondered if he hadn't been too conservative and fussy. Maybe it wasn't Megan Lukens who wouldn't sleep with him. Maybe he wouldn't let her.

The scabrous concierge, the same one who had interrupted

his moment with the Canadian, held open the door. "A la

Seine, la Seine," she sang. He hated that she was

correct. |

| As he lay in his bed, wife beside, baby at the foot in her bassinet, Evan carefully went through the chronology of it. The Canadian was on Friday. No: Thursday. The museum was Friday. |

The girls were eating ice cream. Evie led him down to the

quay. The group remained clustered on the embankment just

above. Evan could hear their voices. He followed her down

the stone steps to the river. The brown water ran past

surprisingly quickly. The flank of Notre Dame, somehow so

feminine, glowed gold. Evie stopped. Her strappy shoes

clattered on the pavement. They pressed together, kissed.

She was fuller and more curved than Megan: softer somehow,

less an arrangement of angled planes. She reached beneath

her filmy skirt, removed her underwear over the heels of

her shoes, and tossed them into the darkness. She clinched

him to her. He thought of something Megan might have said,

blushing and laughing: "What if she had her name in

them?" Lying in bed beside his wife, he remembered it. He had existed in an utter lack of experience, and Evie in what? Her worldliness? Her mature knowledge of her body and its precise mechanism, which would allow her, with this boy, really, to achieve what it was she had drawn him down there for, to Paris for, into her life for, for only these scant few moments of something daring, dangerous, exceptional, but also very vividly lived? He startled in his bed. He must have fallen asleep. A myoclonic jerk. His wife sighed, said something in a dream. The light from his muted table spilled over the bedclothes. The baby made her sleeping noise, a sound Evan equated with ticking. He hadn't been with many women in his life at that point in Paris. When he kissed a girl, he thought that he loved her. It was the look that girls gave when they kissed. It was love and he did fall in love and consequently, since it was love each time, there weren't that many girls. Megan Lukens. Evie Lloyd. Now that he had a daughter, he found himself thinking about them all the time. When Evan got back to Baltimore, he and Megan did not travel to Michigan together as planned. They did not spend a weekend at her grandparents' cabin near Pictured Rocks. Megan changed her major. There were rumors that she was seeing a T.A. There were rumors that she was seeing a professor. That was all Evan knew. He wouldn't let people tell him any more. Evan scrabbled with his right hand along the ancient embankment wall for some purchase. There was a chink, a gap that needed to be pointed between the huge stones. He wedged loose a bit of mortar. It clattered down to the cobbles beneath their feet. He held himself as still as he could; she pressed against him firmly but otherwise hardly moved. Beneath his palm he felt the dampness of the worked stone, coated in a patina of Parisian moss. In his mind's eye he bracketed the equation: An emulsion moving liminally. Curl v: the partial derivative of the vector. Bernoulli's law. Fluid within a pipe. Pipe within a shaft. Viscosity — a venturi tube. "Don't," she said. He tried to arrange the equation in his head, to follow his usual method to a solution. Make a first order system out of a second order equation. For a moment, he paused from his mental arithmetic. It meant leaving an equation unsolved, but allowed him to feel the moment that he found himself in. He awoke from his calculations to a screaming shear, an outrageous transport resistance, the savage howling of nature just outside the window. Everything began falling away: himself, Evie, the ancient and damp wall behind her, Paris, France, Megan Lukens, Soren and Kurt back at the hotel, the girls who chattered, perched on the abutment far above, licking their ice creams. An electric bell sounded. The alarm on his cell phone that sat beneath the dimmed light on his nightstand. Baby's next feeding. Evan muted it and lay back. He was not now even the age that Evie was then. His wife stirred, began to prepare. What was it? Love forgotten? A unique act of animal release? Just a moment in Paris? Had she done it before? Did she again? He felt something like an elastic snap. "Okay," she said. "Time to go." And he did. Tristan Davies, A&S '87 (MA), is a faculty member in the Johns Hopkins Writing Seminars and author of the fiction collection Cake. This story will be included in Davies' forthcoming collection, Forecast (Rager Media, 2008). |

|

|

The Johns Hopkins Magazine |

901 S. Bond St. | Suite 540 |

Baltimore, MD 21231

The Johns Hopkins Magazine |

901 S. Bond St. | Suite 540 |

Baltimore, MD 21231Phone 443-287-9900 | Fax 443-287-9898 | E-mail jhmagazine@jhu.edu |

|