The 2004 Alumni Association Excellence in Teaching

Awards

Just like coaches on a playing field, teachers

sometimes draw on motivational techniques and a hands-on

approach to get the most out of their students. The goal is

knowledge. The opponent, unrealized potential.

Since 1992, the Johns Hopkins Alumni Association has

recognized university faculty who excel in the art of

instruction with its Excellence in Teaching Awards. The

award allows each academic division of the university to

publicly recognize the critical importance of teaching.

The Alumni Association annually provides funds to each

school — this year the amount was $2,000 — that

can be given to one winner, shared by up to four or

attached to another, divisional teaching award. The

nomination and selection process differ by school, but

students must be involved in the selection process.

The following faculty members are recipients of the

2004 Alumni Association Excellence in Teaching Awards.

JOHNS HOPKINS BLOOMBERG SCHOOL OF PUBLIC

HEALTH

Ron Brookmeyer, professor, Biostatistics; medium-size

class

Ron Brookmeyer, professor, Biostatistics; medium-size

class

|

Ron Brookmeyer, Public

Health

PHOTO BY WILL KIRK

|

Ron Brookmeyer gets up suddenly from behind his desk,

strides to the white board on his office wall and with a

marker writes What is statistics? Without thinking, a

visitor immediately writes What is statistics? in a

notebook.

"See? You wrote it down," says Brookmeyer, a professor

of biostatistics, who just won his third Golden Apple

Award, as the alumni award is called in the School of

Public Health. "And you were probably thinking, 'Hmmm?

What's next?' If you're taking notes from the blackboard,

from the discussion, you take ownership of the material

— it's in your handwriting."

Although he now uses computer simulations and the

occasional PowerPoint presentation to teach complicated

statistical concepts, Brookmeyer, who has been teaching at

the school since 1981, still waxes enthusiastic about the

blackboard.

"There's a participation that occurs when you're

working through your lecture together with the class. With

the blackboard, everybody's on a level playing field,

interactive. With PowerPoint, there's not the engagement or

interaction — you'd have read the What is statistics?

slide and said, 'I'll get the handout.' "

Everything Brookmeyer does in class is aimed at

grabbing his students' attention and making sure that the

technical concepts he's explaining are made real for them.

"It's too easy to hang your hat on a formula," he says.

"You have to explain, in a way that's grounded in common

sense, why they're using that formula. Equations are

helpful, but students need to have a gut understanding of

them. Otherwise, the teacher is just hiding behind the

equation."

Students must internalize biostatistical concepts if

they are ever going to be able to apply a statistical

method to new situations, he says. "If the student is only

able to plug data into a formula, that's just a cookbook; a

computer can do that," explains Brookmeyer, who chairs the

school's Master of Public Health Program. "But a computer

can't see how you can apply an old concept in a new way.

The teacher is always trying to show the overall

architecture of the ideas."

And there's an optimal architecture for every message.

"There are lots of messages out there, and the instructor's

job is not to compress more and more information into a

short time or convey a sea of information but rather to

show what's important, what's not, and build to that

architecture."

Finally, Brookmeyer stresses that all teachers must

find their own style, the classroom manner that feels most

comfortable. "You can't fake it or force it," he says.

"Don't try to be something you're not because what works

for some won't work for others. For instance, some are

great at humor ... me, I can't tell a joke."

The Department of Biostatistics offers three unique

biostatistics curricula. An introductory course gives

people the conceptual understanding they'll need to read

scientific papers and tell whether the methods employed in

a study are appropriate. The mid-level course, more

practical and hands-on, is for those who want to analyze

their own data. The most intense and theoretical of the

three, and the one for which Brookmeyer just won the Golden

Apple, is for those who aim to become professional

biostatisticians.

— Rod Graham

Thomas Burke, professor, Health Policy and Management;

small-size class

Thomas Burke, professor, Health Policy and Management;

small-size class

|

Thomas Burke, Public

Health

PHOTO BY WILL KIRK

|

For Thomas Burke, winning this year's Golden Apple was

a great honor because it represents recognition from the

students. He views teaching as his "fundamental calling,"

and it was the main reason he left a career in government

years ago as a public health official for the state of New

Jersey. Since joining the School of Public Health in 1990,

Burke has received three Golden Apple awards for his

teaching. The latest is for his introductory course on risk

science.

"This was a total surprise, but a wonderful surprise,"

says Burke, who is a professor of Health Policy and

Management at the Bloomberg School of Public Health. "It is

great to be recognized by the students, and it's so great

to teach here because the students are so engaged and

motivated. They are the public health leaders of the

future."

Burke teaches Introduction to Risk Science, which is

the principal tool to assess public health risks and turn

that assessment into effective strategies and public

policies. To motivate students, Burke designs the course

around case studies of current public health problems and

issues. This year, students examined the environmental

health impacts of the 2001 attack on the World Trade Center

in New York City.

In addition to teaching, Burke serves as associate

chair of the Department of Health Policy and Management. He

also directs the Center for Excellence in Public Health

Practice, the Center for Excellence in Environmental Health

Tracking and the Risk Sciences and Public Policy

Institute.

— Tim Parsons

John McGready, instructor, Biostatistics; large-size

class

John McGready, instructor, Biostatistics; large-size

class

|

John McGready, Public

Health

PHOTO BY WILL KIRK

|

John McGready, this year's winner of the Golden Apple

teaching award for the large-sized class category, says he

never planned on being a teacher.

Instead, McGready, an instructor in the Department of

Biostatistics at the Bloom-berg School of Public Health,

began his statistical career working as a quantitative

policy analyst at a public policy institute after

graduating from Harvard. It was there that he realized what

he liked doing most. "What I really enjoyed was

communicating with my colleagues and with other agencies,"

he says. "I wanted to up the communication component of

what I did."

Teaching, he says, was the next logical step.

After teaching math at a Washington, D.C., high school

for a year, McGready stumbled upon an ad on the American

Statistical Association Web site for his current Department

of Biostatistics position. "It was just serendipity," he

says. "I never went to that site."

That was five years ago, and this is McGready's second

Golden Apple. He won his first in 2001, for the

medium-sized class category. "Teaching a large class

requires more coordination, more energy, more assistance

and more time," he says. McGready also won the Teaching

Award for Excellence in Distance Education, as voted upon

by distance education students, in 2001.

This year's Golden Apple is for McGready's Statistical

Reasoning in Public Health class, which he teaches both on

campus and online. In addition to time spent teaching class

and with students in office hours, McGready spends much of

his day answering e-mail from students. The e-mail, he

says, is especially important for online students, since it

is the only way to get to know them.

"I like interaction with students from different

backgrounds. I love turning them on to something they can

make germane to what they're working on. I try to explain

things in ways that are as intuitive as possible," he says.

"Also, teaching keeps my own understanding high," he says.

How high? Ever the statistician, Mc-Gready adds, "I

can't quantify how much learning and relearning I've done

in the five years I've been at the school."

— Kristi Birch

KRIEGER SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Jeffrey Brooks, professor, History Department

Jeffrey Brooks, professor, History Department

|

Jeffrey Brooks, Arts and

Sciences

PHOTO BY WILL KIRK

|

Jeffrey Brooks was one of 18 faculty members in the

Krieger School to be nominated for an Excellence in

Teaching Award this year, a field that was narrowed to 10

and from which the selection committee chose Brooks.

"One of the things that was really striking was how

broad a group the recommendations came from," says Adam

Falk, vice dean of faculty and a past winner of an

Excellence in Teaching Award. The nominations for Brooks

came from history majors and nonmajors, from undergraduates

and from graduate students. "They all spoke of his intense

commitment to them personally," Falk says. "He brought out

in all of them their best abilities."

All those nominating Brooks noted how he managed to

help them find the perfect academic project to work on,

because he took time to get to know them. "What you see

with Professor Brooks is an appreciation for a teaching

style focused on relationships," Falk says. "He really got

to know his students, not only as people but

intellectually."

One student who nominated Brooks wrote that he

"masterfully combined close attention to his students' work

progress, vigorous training in research and analysis, and

encouragement to become an independent scholar capable of

choosing one's own agenda and carrying it out."

"I believe that his loyalty to students is his

greatest strength as a mentor," wrote another student,

recommending Brooks for the award.

Another wrote, "He loves his job, and he loves working

with students. Hopkins is very lucky to have such a

brilliant mind and genuinely wonderful person."

— Glenn Small

Also recognized by the Krieger School for their

skills in the classroom were teaching assistants Caline

Karam, Biology; Lars Tonder, Political Science; and Mike

Krebs, Mathematics.

PEABODY INSTITUTE

JoAnn Kulesza, music director, Opera Department

JoAnn Kulesza, music director, Opera Department

|

JoAnn Kulesza, Peabody

PHOTO BY WILL KIRK

|

"If I had to pick one person on the Peabody campus

that has made the greatest contribution to my development

as a professional musician and performer, it would be

JoAnn." Thus began the flood of accolades for JoAnn

Kulesza, this year's recipient for the Excellence in

Teaching Award.

Kulesza has been a member of the Peabody faculty since

1990. As music director of the Peabody Opera Department,

she has been principal coach for productions ranging from

Mozart's Abduction from the Seraglio to Wagner's Walkure,

from Weil's Three Penny Opera to Zimmermann's Die Weisse

Rose, not only coaching but also conducting the latter two.

Her experience and creativity have taken her into

leadership roles as chair of the faculty assembly, the

Self-Report Committee for the National Association of

Schools of Music and the Peabody Committee on Community,

Cooperation and Civility. She freely gives of her time and

energy as a member of these and every other committee on

which she serves.

About her teaching philosophy, Kulesza says she

believes "people live up to the level of expectation that

is given to them" and that she tries to get students to

give "the best that they can give and they can be." For

example, she says, "Music has an integrity in what the

composer wanted," and she doesn't let students lose that

integrity just because they are students. "I tell students

to get to what the composer intended."

When asked about her enthusiasm for volunteering for

nonteaching tasks, she responds, "Peabody is a wonderful

environment. I believe in a holistic approach to the place,

students and faculty. There is no obstacle that can't be

moved with a positive expectation."

To her students, she is not just a provider of

information but a mentor, role model and friend. They know,

Kulesza says, "that excellence in performance is not just

desired but mandatory." At the same time, students

commented that they are grateful that Kulesza is

"organized, efficient, concerned for the well-being of the

students AND a good musician ... a rare combination." She

is "not only artistically and musically phenomenal but also

a human being who truly cares for all students in the Opera

Department."

— Kirsten Lavin

SCHOOL OF ADVANCED INTERNATIONAL

STUDIES

To be announced at commencement.

SCHOOL OF MEDICINE

Theodore M. Bayless, professor, Gastroenterology

Theodore M. Bayless, professor, Gastroenterology

|

Theodore Bayless,

Medicine

PHOTO BY WILL KIRK

|

For Theodore "Ted" Bayless, his ultimate goal in

teaching is to encourage patient-oriented care,

communication and research.

With humanity and reflection, he teaches students,

fellows, junior faculty and even — he might say

"above all" — patients. Taking more time than most

physicians can spare, Bayless teaches his patients about

their disease and its causes, and trainees learn how to

interact with patients by watching him.

"The first question I ask of patients is, 'What can I

do to help?' and then, 'What else should I know about?'"

Bayless says. As a result of this dedication, patients

routinely ask if someone can "clone" him.

Bayless, professor of medicine and director of the

Meyerhoff Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, has influenced

medical education for four decades at Johns Hopkins. He

first got hooked on teaching in the 1960s, when friends who

were house officers asked him to give a couple of guest

lectures. Those lectures led to his co-founding of Hopkins'

Human Pathophysiology course in 1977. He also has

coordinated the basic medical clerkship and curriculum for

many years and is co-director of the continuing medical

education course Topics in Gastroenterology and Liver

Diseases.

His influence extends beyond Hopkins, as he has edited

11 books for practicing physicians and developed

audio-visual teaching materials now used in more than 100

medical schools. "I try to teach as many people as

possible, even if it's not in person," he says.

Bayless says that he appreciates the Alumni

Association's recognition of a commitment to teaching,

which usually comes at the expense of a doctor's family

time.

"I was very lucky to have started my career at a time

when clinicians had more time to balance teaching, research

and patient care," says Bayless, who adds that he's honored

to be among the excellent teachers — past and present

— recognized by the Excellence in Teaching Awards.

"Today, junior faculty almost have to choose between

laboratory-focused research or medical practice with a

heavy patient roster, but awards that focus on education

can encourage junior faculty and fellows to make time to

teach."

He advises the graduating medical school class of 2004

to develop relationships with their patients, to listen,

learn and educate. "Understand why people have particular

symptoms, know which medicines are going to work best and

collaborate with basic researchers," he says. "Ask

questions."

— Diane Bovenkamp

SCHOOL OF NURSING

Susan Appling, assistant professor; baccalaureate

level

Susan Appling, assistant professor; baccalaureate

level

|

Lori Edwards, Sue Appling and

Gayle Page, Nursing

PHOTO BY MING TAI

|

Susan Appling, a 1973 graduate of the School of

Nursing, is now an assistant professor and a nurse

practitioner in the Breast Center of The Johns Hopkins

Hospital. She teaches Principles and Applications of

Nursing Technologies and often can be found moving quickly

back and forth between the school's three skills labs,

where her baccalaureate students practice essential nursing

tasks on manikin "patients." Appling monitors the large

group of students as they learn what she describes as the

"soup to nuts" of nursing — everything from baths to

EKGs.

Appling has the pleasure — and challenge —

of working with students from the very beginning of their

nursing education. "They're anxious and excited," she says.

"I'm teaching the things they classically think of as

nursing, though, and it's definitely a hands-on experience,

so it's not a hard sell."

Working with the new students requires great skill and

compassion, and according to her students, Appling has

both, earning her her fourth teaching award in her 20 years

of teaching. Her students describe her as "warm, welcoming

and sensitive to students" and credit her for "bolstering

... confidence and demonstrating great patience, humor and

insight."

Appling says she feels her job is to work with her

students' strengths, and when she sees their limitations,

to help them strategize ways to overcome them. "By the end

of the course, I want my students to meet the objectives

and learn what they need to know. The bottom line is to get

them there but also to have fun, so hopefully they get

there feeling good about themselves."

— Ming Tai

Lori Edwards, instructor; baccalaureate level

Lori Edwards, instructor; baccalaureate level

One of Lori Edwards' greatest joys of teaching is to

hear from her former students about their lives after

graduation and to find out that she helped them to see the

world in a different way. Many alumni contact her after

graduation, but her students this year didn't wait to show

their appreciation. In April, their nominations earned

Edwards a faculty teaching award.

Edwards teaches students through several courses,

including the popular Complementary/Alternative Health Care

elective, and as coordinator of the school's Community

Outreach Program and Peace Corps Fellows Program. Students

report that she takes the time to get to know them and

"reaches out to and meets each of her students at their

level in a sincere and very heartfelt manner."

She displays a deep commitment to the community as

well. "Our returned Peace Corps volunteers have worked in

remote villages around the world," she explains. "Through

community outreach, I help transition them into working in

an urban environment." Before placing the students in East

Baltimore and the surrounding neighborhoods, she makes sure

they have a clear perspective of the community. "That's my

commitment to the community."

One of Edwards' life goals is to help people and to

inspire them to grow. Her philosophy on teaching is

similar. "Teaching is facilitating students on their

journey of becoming," she says. "It is inspiring students

and leading them to realize their fullest potential.

"We have the best students," she adds. "So it is a

wonderful joy to teach them and share the journey with

them."

Her students have called Edwards "an inspiration to

follow."

— M.T.

Dominique Ashen, assistant professor; graduate

level

Dominique Ashen, assistant professor; graduate

level

|

Dominique Ashen,

Nursing

PHOTO BY WILL KIRK

|

Dominique Ashen wasn't expecting to be named a

recipient of this year's faculty teaching awards. "It was a

wonderful surprise," she says.

Ashen, an assistant professor, teaches pathophysiology

to nurse practitioner students. She works with a diverse

group of about 40 students, some of whom have been nurses

for a while, others who are coming straight from the

baccalaureate program to earn their master's and all with

different experiences and different goals.

"Pathophysiology is a difficult class. There is a lot

of information to learn and integrate, but the students are

very bright and motivated. They are also very oriented to

patient care," she notes. "My goal is to help them think at

a more cellular and molecular level so that they can

understand the basis of disease and the basis of

treatment."

Students consider Ashen an excellent role model

professionally and academically and cite her "enthusiasm to

teach, enhanced by her excellent knowledge of the

material."

A nurse practitioner herself, Ashen spends 60 percent

of her time in clinical practice at the Johns Hopkins

Ciccarone Center for the Prevention of Heart Disease. She

practices both at the Johns Hopkins Outpatient Center and

Johns Hopkins Heart Health at Timonium. "I've always loved

to teach, and I love clinical as well," she says. "I am

very lucky I have been given the opportunity to do

both."

— M.T.

Gayle Page, associate professor; graduate level

Gayle Page, associate professor; graduate level

Gayle Page works closely with doctoral candidates on

their research and teaches small-size classes such as

Philosophy of Science in Nursing. "The interesting thing

about teaching Ph.D. students is that we're on equal

playing fields, so it really is more of an exchange," says

Page, an associate professor. "I learn as much from my

students as they learn from me."

Page's own research is in the effects of pain on the

immune system. Recent studies have shown the importance of

controlling pain in postoperative cancer patients to reduce

tumor growth. Her current investigations delve into the

implications of perinatal and postnatal pain.

Page's goal for her students is for them not only to

think but to be able to support what they think. She

acknowledges that that can be perceived as quite

challenging. "I like to challenge my students," she says,

"so that I can see the wheels churning."

Her students tend to appreciate that challenge. One

noted that Page "walks the fine line between the dual

missions of accepting students for who they are yet never

allowing them to be less than they can be." Another said

she "displays a discerning eye for the unique gifts of

every student and does everything in her power to

facilitate students' achieving their full potential."

Page possesses another attribute so important in

teaching doctoral students. Said another student, "She

fosters a true passion and excitement for nursing

science."

— M.T.

SCHOOL OF PROFESSIONAL STUDIES IN BUSINESS AND

EDUCATION

Ann Kaiser Stearns, Division of Public Safety

Leadership

Ann Kaiser Stearns, Division of Public Safety

Leadership

|

Ann Kaiser Stearns,

SPSBE

PHOTO BY WILL KIRK

|

Ann Kaiser Stearns is in the business of resilience

— specifically human resilience — and how

people overcome and learn from episodes of crisis and loss

in their lives.

Kaiser Stearns, with a master of divinity degree from

Duke University and a doctorate from Union Institute &

University, is in her 34th year of college teaching. She is

a professor at the Community College of Baltimore County

and teaches for CCBC at the Baltimore County Police

Academy. For SPSBE's Police Executive Leadership Program,

known as PELP, she has taught 10 separate courses,

including Developmental Psychology and Theories of

Personality.

"My goal is to take the skills and concepts of

psychology and make them work in public service," Kaiser

Stearns says. "It's been my experience that the police

officers with the best self-understanding and insight into

human behavior make the most effective public servants and

leaders within their forces."

The bulk of Kaiser Stearns' research has been in the

areas of crisis and resilience, specifically studying those

individuals who have faced adversity in their lives and who

have subsequently grown through it. Law enforcement

personnel face "more exposure to extreme events and

resultant stress in the first three years of their careers

than most people do in their entire lives," she points

out.

Kaiser Stearns is the best-selling author of three

books, Living Through Personal Crisis, Coming Back:

Rebuilding Lives After Crisis and Loss and Living Through

Job Loss. Her most recent research on grief management,

published in The Maryland Psychologist, includes "Trauma

Aftermath: Who is Really at Risk?" and "Resilience in the

Aftermath of Trauma and Adversity."

Other recent research centers on the traits police and

other emergency responders possess, how they make decisions

and what perspectives and attitudes most lead to effective

resilience. Components in resiliency that she continues to

study include the importance of emotional and community

support, feeling needed and the importance of work, finding

meaning in suffering, and the strength conveyed through a

sense of faith.

"I find my classes with PELP's police executives most

rewarding and interesting, she says. "Hopkins students are

highly motivated, possess great integrity and represent law

enforcement leaders from across the state of Maryland as

well as Washington, D.C., and other nearby jurisdictions. I

definitely learn as much from them as they do from me. The

longer I interact with police officers, the more I continue

to learn."

Sheldon Greenberg, director of the Division of Public

Safety Leadership, says, "Ann continually receives

excellent reviews from her students. Her dedication to the

law enforcement profession is evidenced by her extensive

work with a number of regional and police departments and

the Concerns of Police Survivors Organizations. This work

directly supports the mental well-being of officers and

their families."

— Andy Blumberg

Deborah Fagan, Graduate Division of Education

Deborah Fagan, Graduate Division of Education

|

Deborah Fagan, SPSBE

PHOTO BY WILL KIRK

|

Deborah Fagan, who has been teaching since 1974,

continues to give back to Johns Hopkins.

In 1991, she was selected as a recipient for a Hopkins

federally funded grant program focusing on inclusion for

students with disabilities. She graduated from the Graduate

Division of Education in 1993 with a master's degree in

Special Education, then began teaching as a faculty

associate.

Ten years later, Fagan is still teaching in the

division's Mild to Moderate Disabilities and Inclusion

programs. She currently teaches three courses:

Instructional Planning and Management in Special Education,

Learning Strategies and Differentiating the Secondary

Curriculum for Students with Mild to Moderate

Disabilities.

Fagan's teaching career, which has included 14 years

in the Montgomery County public school system, has always

involved special education. "I always wanted to teach kids

who faced additional challenges," she says. "It proved very

fulfilling to me, plus I found that I had discovered a

niche area for my talents. Now that I am teaching others

the same skills that I learned and practice, it seems to

complete the circle."

From 1996 to 1999, Fagan was co-director of the

Special Education Teacher-Immersion Training partnership

between Hopkins and Montgomery County. The county school

system hired Hopkins special education degree students as

teaching assistants, then, upon the completion of their

studies, promoted them to special education teachers.

In 1999, Fagan became one of a handful of pupil

personnel workers for Montgomery County public schools,

acting as a liaison between pupils, their families, the

schools and the community. Her experiences in the position,

she says, enrich her teaching.

"I find my Hopkins students are a pleasure to teach,"

Fagan says. "They bring many different backgrounds into the

classroom. Many times these people have already had very

successful careers in business, law or other areas, but

they've always had a passion to teach. They're not

ambivalent about it."

Edward Pajak, associate dean and director of the

Graduate Division of Education, says, "Deborah consistently

receives outstanding course evaluations. However, more than

any numeric score on course evaluations are the comments

that have become standard in describing how her teaching

impacts graduate students' learning — and the

educational experiences they, in turn, provide for students

with disabilities."

— A.B.

Catherine Morrison, Graduate Division of Business

Catherine Morrison, Graduate Division of Business

|

Catherine Morrison,

SPSBE

PHOTO BY WILL KIRK

|

The cornerstone of Catherine Morrison's academic

career was cemented in place by her experience on a factory

assembly line, a summer job she held to finance part of her

undergraduate education. "I learned that I liked to see

things come together, and that a disagreement between

workers anywhere on the assembly line can disrupt

production for the entire plant," she recalls. This

interest would develop into a lifelong study of mediation,

conflict management and negotiation skills for the

practitioner faculty member in the Business of Health's MBA

in Medical Services Management program.

In 1981, while working at the University of Texas

Medical Branch as the administrator for a microbiology

department, she had what she describes as a turning point.

"I loved the complexity of working in an academic medical

center. I wasn't destined to develop a vaccine for cholera,

but every administrative or financial problem that I solved

for one of the faculty freed them up to work on things that

really could potentially change the world," she says. "I

was hooked."

Morrison was also noticing how academic medicine

frequently intersected with law. It was then that she had a

"career epiphany." Believing that lawyers were going to be

the future administrative leaders in health care

management, Morrison headed to law school at the University

of Pennsylvania. She concentrated on transactional law,

learning the legal equivalent of what had captured her

interest on the assembly line — "what it took to make

things work."

After three years practicing transactional law,

Morrison joined the University of Maryland at Baltimore's

academic health, human services and law campus, where she

managed consulting groups that provided IT, internal audit

and management consulting services; served as an adviser to

the vice president for administration on policy, planning

and contractual matters; and assumed management

responsibilities for affirmative action and human resources

matters.

At that time, she began to consider what additional

skills she would need to become a senior leader at an

academic health center. In particular, she sought to gain

experience in clinical management. She learned about a

position as director of administration and finance for the

Department of Pediatrics at Penn State's Milton S. Hershey

Medical Center, and while she was interviewing for the

position, which she ultimately took, the chair of the

Humanities Department in the College of Medicine approached

her about the possibility of teaching part time. "So the

two opportunities came together," she says.

By then, 1993, the escalating costs of health care had

become a national issue, and the use of mediation in health

care was in its early stages. Morrison says she was

intrigued. She "fell in love with conflict management," she

says, during a course in general mediation at the

University of New Mexico Law School. In 1997, she founded

Morrison Associates, a consulting practice providing

strategic advice, negotiation and conflict management.

For the Business of Health's MBA in Medical Services

Management Program, Morrison teaches its required course in

negotiation. She also teaches a similar course for the

Department of Health Policy and Management at the Bloomberg

School of Public Health.

"I love working with SPSBE students," Morrison says.

"I'm so impressed with their energy levels and commitment.

These are people on the front lines of leadership in the

medical field, and we're helping to equip them with the

latest tools they need to do their jobs even more

effectively. We constantly learn from each other."

Douglas Hough, chair of the Business of Health, says,

"Catherine's course evaluations have been exemplary. Her

extraordinary combination of skill, experience and caring

shows in every aspect of her teaching."

— A.B.

George Scheper, Division of Undergraduate Studies

George Scheper, Division of Undergraduate Studies

|

George Scheper, SPSBE

PHOTO BY WILL KIRK

|

George Scheper remembers the first third of his career

as an English professor, happily teaching "traditional"

courses in literature. Then an event happened that, he

recalls, "changed my life."

That event was a 1977 project grant in

interdisciplinary studies from the American Association for

Higher Education. "It transformed me from a 'typical'

English professor to an interdisciplinary humanities

academic," he says. In turn, with a grant from the National

Endowment for the Humanities, he was able to establish the

humanities program he coordinates at the Community College

of Baltimore County.

Scheper, who earned his doctorate from Princeton, has

been teaching for more than 20 years at SPSBE, where he is

a faculty associate in the Bachelor of Science in

Interdisciplinary Studies program.

Scheper says he looks at the subject matter he teaches

as always interdisciplinary in nature in the sense that

what is taught "needs a richer context to be fully

appreciated, so my students can visualize the subject

matter in a more complex, as well as relevant, social

context." His courses have covered a wide range of topics,

including comparative religion; Renaissance Florence; the

Bible and literature; religion and literature; and religion

and art. During his tenure he also has done extensive

research on ancient American civilizations, including

Meso-American and particularly Mayan culture.

In all, he has received seven grants from the National

Endowment for the Humanities, taking 24 college instructors

at a time to Mexico and Guatemala for six-week seminars

that explore archaeological sites, ancient ruins,

contemporary traditional villages, schools and

universities. "It introduces new areas of the curriculum

for us to share among ourselves and with our students."

Scheper says he defines himself as a teacher-scholar.

"There is a phrase from Chaucer — 'gladly learn, and

gladly teach' — that mirrors my philosophy quite

nicely," he says.

Toni Ungaretti, dean of the division, shares some

comments from some of Scheper's students: "Can we have a

Dr. Scheper University?" "I have never worked so hard or

learned so much." "Never let him go."

"These quotes from student evaluations reflect

George's impact on our undergraduate students," Ungaretti

says. "George is a distinguished scholar in ancient

American civilizations, a dedicated faculty member in

Interdisciplinary Studies and a beloved teacher of his

students. He consistently contributes to efforts to ensure

that excellence is the hallmark of our Interdisciplinary

Studies program."

— A.B.

WHITING SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING

Louis Whitcomb, associate professor, Mechanical

Engineering

Louis Whitcomb, associate professor, Mechanical

Engineering

|

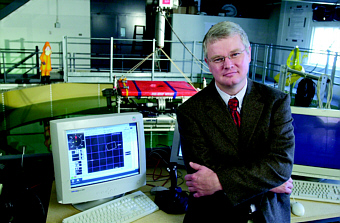

Louis Whitcomb,

Engineering

PHOTO BY JAY VANRENSSELAER

|

In the classroom, Louis Whitcomb, associate professor

in the Whiting School's Department of Mechanical

Engineering, must be doing something right. For the second

time in four years, he's been honored for his teaching

skills.

One of the students who supported his selection for a

2004 Alumni Association Excellence in Teaching Award said

Whitcomb's "interest, enthusiasm and, most importantly, his

ability to incite that same interest and excitement in his

students make him worthy of this award."

Another student added, "He encourages participation in

class, is outwardly cheerful, clear in his teaching and

extremely approachable. I had gone to his office a number

of times ready to give up on a number of things, and

through his encouragement and advice, always left with a

new sense of determination."

In 2001, when Whitcomb received the Student Council

Excellence in Teaching Award within the Whiting School, he

was similarly hailed for his enthusiasm as an instructor

and his devotion to students.

Whitcomb, whose specialties include control systems

for undersea vehicles and medical robotics, has been

participating in a research mission at sea most of this

month, so he was unreachable for comment on this newest

accolade. When he received his 2001 teaching honor,

however, he expressed mild discomfort at being singled out

for his instructional skills. "I think there are a lot of

people at Hopkins who are more deserving," he said. "Within

Mechanical Engineering alone, we have a lot of awesome

teachers." Regarding his enthusiastic teaching style,

Whitcomb said, "If you're not excited about the subject

you're researching and teaching, you should get another

job. If you're interested in the material and you show it,

then the students will be interested, too."

In 2002, Whitcomb obtained funding for and oversaw the

construction of a 43,000-gallon testing tank lab in

Maryland Hall for developing oceanographic research

technology. Whitcomb, who collaborates with the Woods Hole

Oceanographic Institution, involves undergraduates and

graduate students in projects within the new lab.

He joined the Hopkins faculty in 1995.

— Phil Sneiderman

Also recognized by the Whiting School for his skills in

the classroom was teaching assistant Simil Roupe,

Biomedical Engineering.

GO TO MAY 17, 2004

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

GO TO MAY 17, 2004

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

GO TO THE GAZETTE

FRONT PAGE.

GO TO THE GAZETTE

FRONT PAGE.

|