Navigating New Waters

Trevor Adler, here on the

Constellation, combined his history and maritime interests

to research the raising of ships.

PHOTO BY HPS/WILL KIRK (except

where indicated)

|

PURA grants launch 41 undergraduates into a sea of research

projects

In its 11-year existence, the

Provost's

Undergraduate Research Awards program has given 483

students grants approaching $1 million to follow their

curiosity, thanks to funding primarily from the Hodson

Trust.

With Hodson support, the university is able to offer

its undergraduates two opportunities each year to apply for

stipends to conduct independent research during the summer

or fall. It's a commitment that the university feels is

central to its mission, said Steven Knapp, university

provost and senior vice president for academic affairs.

"Since its beginnings, Johns Hopkins has always

emphasized the value of learning through discovery, and

this program is an important opportunity for undergraduates

to work in this tradition with our best and most creative

faculty at the forefront of their fields," Knapp said.

Forty-one students from the schools of Arts and

Sciences, Engineering and Nursing and from Peabody will

present their work from 3 to 6 p.m. on Thursday, March 11,

in the Glass Pavilion at Homewood. The entire Hopkins

community is invited to the event, which begins with an

informal poster session allowing students to display and

talk about their projects. At 4:15 p.m., PURA recipient

Katherine McDonough and others will a perform a piece by

Jean Baptiste Leclerc, a writer/politician/composer during

the French Revolution and the focus of McDonough's

project.

An awards ceremony hosted by Knapp will begin at 4:30

p.m. and will be followed by a reception. As part of the

ceremony, guests will hear a preview of recipient Daniel

Davis' historically based opera, which will premiere at

Peabody.

By design, PURA grants are driven by students'

interests and cover a wide range of topics. The 2003

projects are no exception. A sampling follows.

Raising ships

In his PURA proposal, Trevor Adler put it this way:

"From maritime historians to oceanographers, from sailors

to sea-loving landlubbers, and from adults to children, the

subject of sunken ships, their discovery and their raising

are subjects that excite many a reader." And especially

Adler, a senior history major who grew

up on New York's

Long Island.

In a course on the Civil War taught by Michael

Johnson, Adler became interested in the several U.S. and

Confederate ships that were sunk and then raised, and he

became intrigued not only by the methods used but also by

the motivations behind raising them.

So last summer, Adler spent six weeks at the Munson

Institute of Mystic Seaport in Mystic, Conn., home to the

largest maritime library in the United States, with some

65,000 volumes and more than 700,000 manuscripts.

It was here that Adler found detailed correspondence

on the efforts to raise three ships, two English and one

Swedish. What Adler learned is that the motivations to

raise the ships didn't necessarily stem from financial

considerations.

The Mary Rose, an English warship named for King Henry

VIII's sister, was the king's favorite war vessel. It sank

during an engagement with the French in 1545, but not

because it was damaged in the battle. Essentially, the ship

was turned too quickly and heeled over, taking on water and

sinking, all within sight of land and the Portsmouth

Harbor, where King Henry himself watched.

"It was a ship that really meant something to the

king," said Adler. And that was the main reason crews tried

to raise it, which they did by attaching ropes to the

sunken ship from two other ships at low tide, in hopes of

floating it free. It didn't work. In fact, of the three

ships that Adler studied, all raising efforts failed. "It

was almost pathetic to try to raise ships of this size,

loaded with cannon, with pulleys and the tides," Adler

said. "But they tried."

Michael Johnson, whose class had piqued Adler's

interest in the subject of raising ships, said about his

work, "He's extremely thoughtful. He's creative and

imaginative, and he's extremely disciplined. I think his

research skills are superb."

Adler, whose sponsor was John Russell-Wood, hopes to

attend law school and study maritime law.

— Glenn Small

Historical shadow

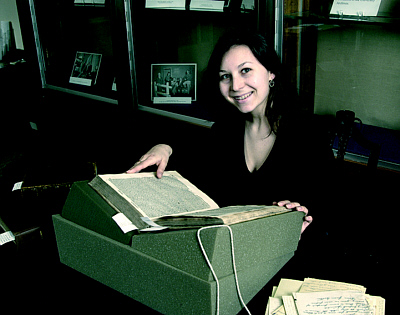

HISTORICAL SHADOW: Ashley Horton

examined the life of Marie-Anne Lavoisier, the little-known

wife of Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier, the father of modern

chemistry.

|

Marie-Anne Lavoisier has gone down in history as her

husband's wife. But senior Ashley Horton believes

Marie-Anne may be important beyond her relation to

Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier, the father of modern chemistry.

Horton, who is majoring in public health studies, used her

PURA to piece together a portrait of Marie-Anne Lavoisier

apart from her husband.

Lawrence Principe, Horton's sponsor and a professor in

the Krieger School's Department of

History of

Science and Technology, said of Lavoisier, "She's not just an

attachment to her husband. She is a fascinating individual

in her own right, and that is what Ashley is trying to

bring out."

Horton has learned that Marie-Anne was not only key to

Antoine-Laurent's work but was also a societal and

political figure in 18th-century France. "I'm interested in

the role she played in Lavoisier's work and to what extent

she was important in his relations with English science,"

said Horton. "He spoke [English] very poorly, and read it

very poorly, so any important treatises she translated into

French."

Marie-Anne Lavoisier also helped smuggle research to

her husband during his imprisonment in Revolutionary France

and, after his execution, led a public and political attack

against the government when it confiscated her property.

But since she has always been a historical shadow,

Horton had to learn archival tricks and search widely for

information, visiting museums and archives from Wilmington,

Del., to Paris. "It's always a problem when you're

searching for someone in the shadows," she said.

Horton, who plans to go into laboratory research when

she graduates, became interested in Marie-Anne Lavoisier

when she took a class called Lives in Science taught by

Daniel Todes.

Her PURA research, she said, has allowed her to move

away from her background in lab research and molecular

biology. "It's given me a more well-rounded education," she

said. "I've taken a lot of chemistry, and it is really nice

to see the humanities side of it."

She also has learned the technological advantages

enjoyed by modern researchers and scientists. "Learning

more about the history of science has given me a real

appreciation of where science is now and the whole

progression of it," she said.

Horton plans eventually to write a short biography

about Marie-Anne Lavoisier. "I think it would be a

bestseller," Principe said.

— Jessica Valdez

STD testing for women

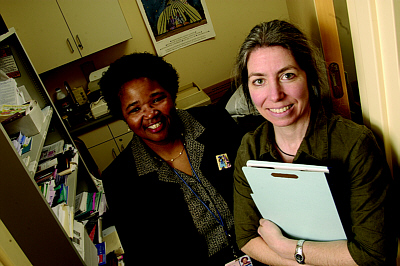

SDT TESTING FOR WOMEN: Megan

O'Brien Gold, right, and sponsor Phyllis Sharps at the Wald

Community Nursing Center at the House of Ruth, site of her

PURA project.

|

Nursing student

Megan O'Brien Gold's project involved

21 women at the House of Ruth, a shelter for female victims

of domestic violence. It is one of several sites that

houses a Wald Community Nursing Center run by School of

Nursing faculty and students. Gold works there as part of

the school's community outreach program.

All women who come to the House of Ruth are seen

initially at the center to familiarize them with its

nursing services, which currently include screening for

sexually transmitted diseases through cervical swab, if a

woman requests it. Knowing that previous research has

linked abusive relationships with increased rates of STDs

among women, Gold explored changing the protocol for

screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia, the most frequently

reported infectious diseases among men and women.

"Women with undiagnosed and untreated infection are at

risk for significant gynecologic problems and increased

risk of HIV transmission," Gold said. "Many of the women we

see at the clinic are not receiving medical attention.

Ideally, every one of them should be offered urine

screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia."

Armed with her PURA, Gold set out to determine two

things: the prevalence of gonorrhea and chlamydia among

women at the shelter, and the acceptability of universal

urine screening. The results of Gold's project were just as

she expected. One woman of the 21 tested positive for

chlamydia, or roughly 5 percent of the study sample,

slightly more than the average of 3 percent for female

Baltimore residents ages 18 to 35. "I wasn't expecting it

to be more, but the results are enough. Now we have the

data we need to validate the implementation of universal

screening," Gold said.

In addition, Gold reports that the women were very

willing and interested in participating and were favorable

to the urine-testing method of screening. "The urine test

is not expensive, and it's noninvasive," she said, noting

that treatment for these diseases is far more costly than

the cost of urine screening.

Gold's faculty sponsor, Phyllis Sharps, is pleased

with the project. "The results of Megan's research have the

potential to change nursing practice in our clinic," said

Sharps, associate professor and director of the school's

master's program. "This could lead to implementing a

quicker, less expensive and accurate method for screening

for STDs and to improving health outcomes for the women who

come to the House of Ruth."

— Ming Tai

Music in 18th-century France

MUSIC IN 18TH-CENTURY FRANCE:

Katherine McDonough, right, worked with sponsor Susan Weiss

on a project that took her to Paris for six weeks of

research.

|

Regulations imposed by the Republican government

during the French Revolution affected many aspects of

France's 18th-century life. The government's attempt to

regulate the music of that period is the focus of research

conducted by sophomore Katherine McDonough, a history and

French major in the

Krieger School. Thanks to her PURA,

McDonough spent six weeks of her summer in Paris in the

music and manuscript divisions of the Bibliotéque

Nationale

de France and the Archives Nationales.

McDonough's attention to French Revolutionary music

began with a chance encounter. While visiting the Oberlin

Conservatory during high school, she had picked up a book

that focused on just this subject. At Johns Hopkins, she

honed her research skills and continued to build her

knowledge of the French Revolutionary period. In the fall

of 2002, she enrolled in a course called From the Court to

the Boulevard: French Theatre and Opera, taught by Nicole

Asquith.

Her final paper in that class focused on an essay

written in 1796 by Jean-Baptiste Leclerc, a member of the

Convention during the Revolution. In his essay, Leclerc, a

lesser-known composer, called for the government to develop

a canon of French national music and to censor the existing

music performance system.

McDonough studied the writings and musical composition

of Leclerc while in France and plans to continue searching

for reviews of his work and evidence that he may have

written more. "Since this project is in the field of

music, my 10 years of classical piano and violin training

will prove extremely useful," she said.

McDonough worked closely on this project with Susan

Weiss, a musicologist at Peabody.

"It is rare to find a student interested in the

history of the impact of political theory on culture, one

gifted enough to be able to read and digest documents in a

foreign tongue, and have the proficiency to understand the

technical language of music theory and composition," Weiss

said. "Katie's work will become a model for others

interested in doing interdisciplinary research."

— Kirsten Lavin

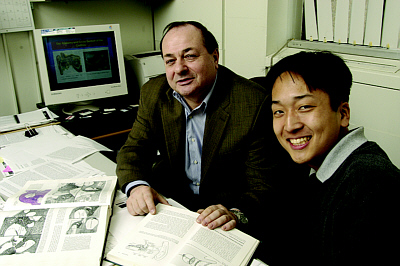

The artistic autistic

THE ARTISTIC AUTISTIC: Vandna

Jerath and sponsor Tristan Davies look at the Web site

Jerath developed to showcase the creative works of autistic

people.

|

On paper, junior Vandna Jerath's major and minor,

neuroscience and Writing Seminars,

are at opposite ends of

the academic spectrum. But the two disparate disciplines

meet online at the junior's newly created Web site, Autism

Netverse: A Literary Journey for the Autistic Mind,

www.jhu.edu/netverse.

Jerath's PURA project provides an artistic forum for

people with autism who often find it easier to express

themselves through writing and visual arts than through the

spoken word. Visitors will find poetry, sketches, paintings

and photographs by people of all ages.

She was inspired to seek a PURA grant to launch Autism

Netverse after conducting research in summer 2002 near her

hometown of Martinez, Ga., with neuroscientist Manuel

Casanova, then of the Medical College of Georgia, now of

the University of Louisville, where he holds the Gottfried

and Gisela Kolb Endowed Chair in Psychiatry. Her assignment

was to compile an anthology of poetry by highly functioning

autistic individuals.

She found the project rewarding and wanted to take it

further by persuading journals and nonprofit groups to

dedicate sections of their publications to the creative

works of autistic people, but didn't have any luck in the

endeavor. Jerath, who also conducts autism research with

Stewart Mostofsky at the Kennedy Krieger Institute, didn't

want to wait any longer for others to decide her idea had

merit. Thanks to PURA, Jerath was able to strike out on her

own and create Autism Netverse.

"I realized that I didn't need a degree to make an

impact on the autistic community," said Jerath, who intends

to pursue a career in medicine. "The provost grant provided

me with this opportunity. If I hadn't explored the concept

behind the Web site, someone else surely would have in the

future."

On the Remarks page of Autism Netverse, Casanova

explains that Jerath's Web site "encourages those suffering

from autism to write and publish their poetry

electronically. After seeking and failing to find other

media outlets for this art form, she received grant support

to fill this niche herself. Her effort is audacious, akin

to building an airplane while flying it."

Jerath said the project took a little while to get off

the ground. With guidance from her PURA adviser, Tristan

Davies, a senior lecturer in the Writing Seminars, Jerath

was soon in touch with Patricia Kramer and Web designer

Megan Van Wagoner of the university's

Office of Design and

Publications and also had secured a domain name

through the university. Seeking writers and artists,

she sent out

letters to physicians and researchers, and after some

watchful waiting, ultimately received 30 submissions from

as far away as India.

"Vandna is an exceptional person," said Kramer,

director of Design and Publications. "Her passion and

dedication to her endeavor are impressive. Her genuine

enthusiasm is catching, and we caught it. If this is our

next generation, we don't have anything to worry about."

In addition to consultations with Kramer and her staff

and with Davies, Jerath is working with Doug Basford of the

Writing Seminars, who has provided additional insight on

the poetic submissions, she said. "Analyzing the works may

provide clues about the thought process of individuals with

the condition."

Davies said he thinks "the idea can't really lose. It

will be of interest to the general public for the obvious

reasons. There might even be some interesting writing that

gets found there. It's a glimpse into this very confusing

world. Certainly, it's got to be a tool for parents [of an

autistic child] who are struggling with this, by providing

hope that there's something that their child might connect

to. Finally, it shows the perfect union of three things:

the humanities, scientific research and technology. It's a

Web site that might really make a difference."

— Amy Cowles

Earthworms and infiltration

EARTHWORMS AND INFILTRATION: Scott

Pitz spent the summer in the field learning about the

effects of management processes and seasonal changes on

farmland.

|

Scott Pitz used his PURA grant to study earthworms.

Pitz set out last summer to research how different soil

management practices and earthworms affect farmland

infiltration.

"There are different earthworm communities in

different fields," he said. "I wanted to see if the

different earthworm communities would affect

infiltration."

Through fieldwork at the USA-ARS Farming System

Project in Beltsville, Md., he learned that worms and

infiltration are affected by management processes and

seasonal changes.

"We kind of showed again that management affects the

earthworms, and earthworm burrows drastically affect

infiltration," he said. Land use — till or no-till

farming — influences the size and species of

earthworms present in fields, which in turn affects

earthworms' impact on soil and infiltration.

Pitz sampled corn plots in three cropping systems: a

synthetic no-till, a synthetic till and an organic system.

He used two processes to evaluate how well the soil

absorbed water: sprinkle infiltration (which simulates

moderate rainfall) and ponded infiltration (which simulates

heavy rain).

He also evaluated the impact on earthworms.

"Earthworms basically are the most important soil

invertebrates," he said. Their burrowing habits are key to

soil infiltration and can help reduce run-off and pesticide

leakage into surface water sources. But tilling disrupts

earthworm communities by destroying their burrow, he said.

Pitz's effort was part of a larger project conducted

by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which is looking at

how agricultural practices in the mid-Atlantic can be

sustainable. His project adviser, Katalin Szlavecz, a

senior lecturer in

Earth and Planetary Sciences, is

studying invertebrate communities on these fields.

Pitz had done lab research with Szlavecz, but this was

his first time dealing with the inconsistencies of

fieldwork. "It's not cut and dry; it's not a chem lab where

there's a set number of variables," he said.

Szlavecz said that Pitz's PURA gave him an opportunity

that most undergraduates lack. "I think the students here

don't get a lot of field exposure," Szlavecz said. "Now he

likes fieldwork better than lab work."

— Jessica Valdez

Egyptian dig

EGYPTIAN DIG: Kathelene Knight

spent winter break working at Professor Betsy Bryan's

excavation of the Precinct of the Goddess Mut in Luxor,

Egypt.

PHOTO BY HPS/JAY

VANRENSSELAER

|

Kathelene Knight's PURA funded her second winter break

at Professor Betsy Bryan's annual excavation of the

Precinct of the Goddess Mut in Luxor, Egypt, where she

contributed to the ongoing work to determine what the

temple and its surrounding area looked like long ago.

Knight said her work in Luxor barely scratched the

surface of all there is to be uncovered at the site. Yet

the two large granaries found within Knight's excavation

trenches south of the temple's sacred lake are important

finds, according to Bryan, the Alexander Badawy Professor

of Egyptian Art and Archaeology and chair of the

Near Eastern Studies

Department.

"These storage facilities are among the largest found

in Egypt," said Bryan, who is Knight's faculty sponsor.

"The two in Katie's squares, one of which was already known

to us but the other not, have been beautifully defined as a

result of Katie's work."

In January 2003, Knight was a second set of hands for

graduate students as they worked their squares, generally

doing anything and everything to pitch in and learn more

about the archaeological techniques used by Bryan and

company. That hands-on experience was invaluable this year

when Knight's role was to direct work in two trenches

— first in a square that had been opened last year

and then in a new square. While taking nonstop notes on her

site's progress, Knight directed a crew of local workers

led by "gufti" Mahmoud Abady who was trained in archaeology

in the Egyptian town of Guft.

"He's known on site as 'Super Gufti,' and I'm sure

there was no mistake in pairing the two of us," Knight

said. "He can spot mud brick from 3 centimeters before it

would come up, and we're talking about spotting dirt inside

dirt."

The two granaries unearthed by Knight and her team

were typically used to make beer and bread for religious

offerings and personnel rations. While the area south of

the sacred lake was industrial and probably partly

residential, the specific area directed by Knight turned

out to be entirely industrial, Bryan said. Because the

mission of the excavation is to investigate the New

Kingdom, Knight was working to define occupation in her

square for that period of time, 1550-1069 B.C. She received

guidance from both Bryan and Violaine Chauvet, a graduate

student and field director at the site.

"Katie did a remarkably fine job overseeing the

excavation," Bryan said. "Katie kept on top of the

architecture emerging and documented her trench extremely

carefully. She participated in developing excavation

strategies to better define the emerging granaries and

retaining walls, and she has created a plan to aid in our

prediction of the volume of grain stored in the round

silos."

Because she is a resident adviser at Homewood, Knight

had to leave Egypt before the end of winter break to return

to Baltimore for additional training. She was unable to

complete all her drawings and was therefore assisted by

Chauvet. Her help was just one example of the close-knit

ties between those working the site, Knight said.

"Dr. Bryan and Violaine were making the rounds

constantly. I could count on them to be in my square a few

times during the day advising me what to do, what I should

be looking out for," Knight said. "It's really a familial

learning experience."

Knight, a junior, is already incorporating her study

of the New Kingdom into a master's thesis through the

Humanities Honors program. She's concentrating on the role

of royal women in the New Kingdom and aims to graduate in

spring 2005 with bachelor's degrees in both anthropology

and Near Eastern studies as well as a B.A./M.A. in the

humanities. Her plan is to complete her thesis during next

year's winter break, so it's unlikely Knight will be back

in Egypt then. But she hopes to attend field school in Peru

this summer with the assistance of a second PURA grant.

"As an undergraduate lucky enough to be at an

institution like Hopkins, I have this wonderful

opportunity, and it's really cool that I can take it," she

said of her PURA experience. "It's an incredible

opportunity that I'm totally thankful for."

— Amy Cowles

Mysterious inner-ear hair cells

MYSTERIOUS INNER-EAR HAIR CELLS:

William Hsu, right, has been doing research with Alexander

Spector for two years. He hopes to publish his PURA

results.

|

William Hsu, a senior from Westlake Village, Calif.,

is playing an important role in solving the mysteries

surrounding tiny hair cells in the inner ear that help

humans distinguish between high-frequency sounds, an

ability that is critical for understanding speech. The work

could lead to a better understanding of age-related hearing

loss and to the improvement of hearing aids.

Hsu has been working on the research under the

supervision of Alexander Spector, an associate research

professor in the

Department of

Biomedical Engineering,

since his sophomore year. Last fall the BME major used a

PURA to devote more time to the project, with the goal of

publishing results in a peer-reviewed journal.

"William's educational path here was related to his

research," said Spector, his PURA faculty sponsor. "I

encouraged him to take classes relevant to this research.

He's become more and more involved in the project, and now

he has his own piece of it. I plan to submit his work to a

scientific journal by the time of his graduation."

Spector directs a team of students who have been

studying the outer hair cells of the cochlea, a

snail-shaped, fluid-filled structure within the inner ear.

Sound waves vibrate through the cochlear fluid and excite

clusters of hair cells in the surrounding membrane. Inner

hair cells pick up sounds and turn them into electrical

signals that zip across nerve fibers to the brain. Mammals,

including humans, also possess outer hair cells, whose

purpose puzzled researchers for many years because these

cells cannot send sound messages to the brain. In 1985,

however, scientists learned that outer hair cells in the

lab changed their length when subjected to an electric

field. When these hair cells are within the cochlear

membrane, this size-changing characteristic is believed to

give them the ability to amplify certain sounds before the

sounds are transmitted to the brain.

According to Hsu, "these outer hair cells help us

discriminate different frequencies, and that's critical in

understanding human speech. But these hair cells are

delicate. As we age, they can deteriorate and become less

sensitive, leading to hearing loss."

To address this problem, researchers need a better

understanding of how outer hair cells do their work.

Spector's team has been trying to solve some of the

mysteries surrounding why the electrical activity of these

cells seems to behave differently in the lab than within

living tissue. As part of this project, Spector assigned

Hsu to create mathematical models of the ionic channels in

the outer hair cell membrane. These microscopic gatekeepers

allow ions to move in or out of cells, changing the cell's

overall electric potential. By varying the parameters of

the computer model, Hsu is trying to find the combination

that will resolve the cell's electrical activity

paradox.

"Working with Dr. Spector has given me a different

perspective on research," Hsu said. "When I came to

Hopkins, I thought research involved sitting behind a lab

bench, working with chemicals. I didn't know that research

could involve creating computer models. I've learned that

we can do experiments with them. We can play around with

our models and see how well they predict what happens in

the actual cells."

— Phil Sneiderman

Researching international justice

RESEARCHING INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE:

Amanda Leese headed to The Hague, Netherlands, to observe

trials in the International Criminal Tribunal.

|

Amanda Leese, a sophomore, spent three weeks last

summer in The Hague, Netherlands, researching international

justice by observing and interviewing those involved in

trials in the International Criminal Tribunal.

The international relations major was there to observe

the trial of Slobodan Milosevic, the former president of

Yugoslavia, who is defending himself on charges of

committing war crimes and other atrocities. At the

International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia, Leese was

among each day's spectators watching through thick

bulletproof glass while listening to testimony on

headphones. Each member of the public was given a

translating device, which could be set on the language of

his or her choice, she said. Without the headphones,

nothing could be heard through the thick glass, giving her

a detached feeling, she said.

She was surprised, she said, that more people didn't

observe the trial, which is still going on; with room for

about 80 spectators, Leese said, there were usually just 15

to 20 people, not counting the press.

Although the most sensitive testimony was closed to

the public, Leese heard hours of testimony from people

describing firsthand the atrocities they had seen or

endured, an experience she likened to "listening to Anne

Frank read from her diary."

Leese, whose faculty sponsor was Siba Grovogui, is

hoping to return to The Hague this summer to learn

more.

— Glenn Small

Healthy heartbeat

HEALTHY HEARTBEAT: Bhuvan

Srinivasan, right, with his PURA faculty sponsor, Andre

Levchenko, and Carol Xiaoying Koh, who also works on the

research team.

|

Bhuvan Srinivasan and Carol Xiaoying Koh are mapping

the interaction of molecules within a cardiac cell,

describing microscopic movements that could be critical for

maintaining a healthy heartbeat. The two undergraduates,

both biomedical engineering majors, have presented their

findings at prestigious computational biology conferences

and are now collaborating with their faculty supervisor on

a paper for a scientific journal.

Working in the lab of Andre Levchenko, an assistant

professor in

Biomedical Engineering, the two have been

tracking within a detailed computer model the activity of

molecules in a small region inside cardiac myocytes, the

muscle cells that mediate contractions of the heart.

"The contraction of the myocytes is controlled by tiny

sub-sections of the cell with a volume so small that you

could count some of the molecules present there on one

hand," Levchenko said. "But by modeling the interaction

between single molecules in these areas, we think we can

predict what's going to happen to the entire heart. What

happens here sets off a chain reaction of events leading to

heart contraction."

Levchenko is impressed by what the two undergraduates

accomplished in assembling part of this model. "The level

of work done by Bhuvan and Carol is close to that of very

good graduate students," Levchenko said. "I've given them a

little advice, but they've mostly run with it by

themselves. They're exceptional students. I've sometimes

come into the lab at 3 a.m. and found them working on the

project."

Srinivasan has been working in Levchen-ko's lab for

two years and used a PURA to devote additional time to the

project last summer. Koh, who has been working in the lab

for more than a year, is supported by a scholarship from

the government of Singapore. The two students attended the

same high school in Singapore but were not acquainted

before they arrived at Johns Hopkins.

Over the past year, they worked on separate aspects of

the research, then put their findings together. Koh has

defined and spearheaded the project by gathering various

information from the literature and coding it into the

modeling software. Srinivasan assembled a computer model of

the protein kinase A pathway, a communication route along

which signals move between the outside and inside of the

cell. The model can now describe molecular events arising

from both signaling and cell contraction regulation. "Now

we can ask, What if something happens to this pathway?"

Levchenko said. "How would it affect the interaction of

molecules within the cells, and how would this affect the

contractions of the heart as a whole?"

In the fall, Srinivasan presented some of the team's

work at the NIH Digital Biology Conference in Bethesda,

Md., where the poster was singled out as a highlight of the

meeting. Koh traveled to Washington University in St. Louis

to present the research at the International Conference on

Systems Biology, the premier event in the emerging

scientific field. Both were surprised to discover that they

were the rare undergraduate presenters, fielding questions

from prominent full-time researchers, including some whose

work they had studied.

Although Srinivasan is not scheduled to receive his

bachelor's degree until May, he already has begun working

toward his master's degree in biomedical engineering at

Johns Hopkins. "It was definitely a big deal for me to come

to America's first research university," said Srinivasan, a

citizen of India whose family relocated to Singapore when

he was in sixth grade. "It's been very easy to get involved

in research here and to do something worthwhile — not

just cleaning lab equipment. I liked working with Dr.

Levchenko, and I wanted to stay as long as I could."

— Phil Sneiderman

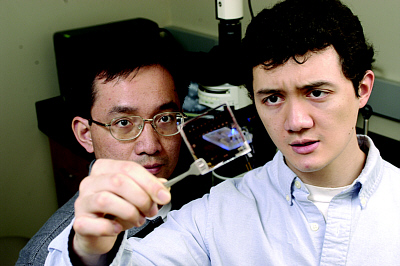

A new microchip

A NEW MICROCHIP: Eric Simone,

right, holds up the microchip he constructed under the

supervision of Jeff Tza-Huei Wang. It has an innovative

circular electrode design.

|

Eric Simone, a senior

biomedical engineering major,

has constructed a new type of microchip that can move and

isolate DNA and protein molecules. He believes that by

linking the chip with analysis equipment, a user could

identify medical ailments, monitor a patient's health or

detect viruses and other biohazards before they spread.

Simone fabricated and tested the chip in the lab of

Jeff Tza-Huei Wang, an assistant professor in the

Department of Mechanical Engineering. Wang had already

produced a biosensor chip with electrodes embedded in a

straight line. Under Wang's supervision, Simone devised a

biosensor chip with an innovative circular electrode

design, which performed more effectively in certain

bio-analytical applications.

Results from Simone's work were included in a paper

presented recently at the IEEE MEMS Conference. The

undergraduate was listed as second author on the paper.

"This chip gives us a new tool to look into biological

questions," said Wang, who also is a faculty member of the

Whitaker Biomedical Engineering Institute at Hopkins. "Eric

can actually interact with and manipulate individual DNA

molecules."

Simone joined Wang's lab team in January 2003 and used

a PURA to spend much of last summer working on his project.

"The chip has tiny wires, each about one-fifth the diameter

of a human hair, embedded in a circular pattern," Simone

said. "When it's connected to a power source, it allows us

to generate an electric field that can transport molecules

to a designated area for study."

The chips made by Wang and Simone take advantage of

the natural negative charge possessed by DNA or a surface

charge imposed on the molecules. A tiny drop of liquid

containing the DNA is placed atop the chip. The electric

field then guides the molecules to the designated area,

where they can be analyzed under a microscope.

Simone was one of the first students to work in Wang's

new lab, which focuses on microelectromechanical systems

with biological applications. "It was fascinating," Simone

said. "It was like discovering a whole new field of

science."

After graduating, Simone hopes to continue his

education in a biomedical engineering doctoral program.

— Phil Sneiderman

The 11th Annual PURA Ceremony: Check Out Their

Results

To recognize the recipients of the 2003 Provost's

Undergraduate Research Awards, an event will be held from 3

to 6 p.m. on Thursday in Homewood's Glass Pavilion.

A poster session in which students will have an

opportunity to display the results of their research begins

at 3 p.m. At 4:15 p.m., recipient Katharine McDonough and

others will perform a piece by Jean Baptiste Leclerc, a

writer/politician/composer during the French Revolution and

the focus of McDonough's project.

At the 4:30 p.m. recognition ceremony hosted by Steven

Knapp, provost and senior vice president for academic

affairs, Knapp will introduce the honorees, and Theodore

Poehler, vice provost for research and chair of the

selection committee, will present the students'

certificates. Also on the agenda is a preview of Daniel

Davis' historically based opera, which will premiere at

Peabody.

The entire Johns Hopkins community is invited.

SUMMER 2002 PROJECTS

Trevor Adler, Sands Point, N.Y.

senior, history

"Historical Research of the Methods and Motivations for

Raising Ships"

Sponsor: John Russell-Wood, professor, History,

Krieger School of Arts and

Sciences

Oluwakemi Ajide, Baltimore

sophomore, chemistry

"Dynamics of the Fusion Pore During Cell-Cell Fusion"

Sponsor: Eric Grote, assistant professor,

Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, School of Public

Health

Tala Altalib, Baltimore

junior, undeclared

"Modulation of TNF-Alpha Expression in Human Chondrocytes

and

Synoviocytes by NSAIDs and Ginger Extract"

Sponsor: Carmelita Frondoza, associate professor,

Orthopedic Surgery, School of Medicine

Heather Blair, Norfolk, Mass.

senior, public health studies

"Mapping the Prevalence of HIV Against That of Tuberculosis

in

Johannesburg, South Africa"

Sponsor: James Goodyear, associate director, History

of Science and Technology, Krieger School of Arts and

Sciences

Megan O'Brien Gold, Baltimore

senior, nursing

"Universal Urine Screening for Neisseria Gonorrhoeae and

Chlamydia Trachomatis Among Battered Women"

Sponsor: Phyllis Sharps, associate professor and

director of the master's program, School of Nursing

Ashley Horton, Spokane, Wash.

senior, public health studies

"Marie-Anne Lavoisier: A Woman of Scientific and Cultural

Importance"

Sponsor: Lawrence Principe, professor, History of

Science and Technology, Krieger School of Arts and

Sciences

Brett Kutscher, Reading, Pa.

senior, computer enginering

"Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching

Instrumentation"

Sponsors: Doug Murphy, professor, Cell Biology, School of

Medicine, and Pablo Iglesias, professor, Electrical and

Computer Engineering, Whiting School of Engineering

George Lambrinos, Athens, Greece

junior, neuroscience

"The Role of Wallerian Degeneration in the Pathogenesis of

Neuropathic Pain Following Peripheral Injury"

Sponsor: James Campbell, professor, Neurosurgery,

School of Medicine

Adrea Lee, Andover, Mass.

senior, biology

"The Role of Fractalkine in the Pathogenis of HIV

Dementia"

Sponsor: Carlos Pardo-Villamizar, assistant

professor, Neurology, School of Medicine

Johnson Lee, Arcadia, Calif.

senior, biology

"Smooth Muscle Differentiation of Human Embryonic Stem

Cells (hESCs)"

Sponsor: Yegappan Lakshmanan, assistant professor,

Urology, School of Medicine

Amanda Leese, Amherst, N.H.

semior, international studies

"Human Rights Violators and the International Court of

Justice: Contrasting the Barbarity of Crimes with the

Dignity of Laws"

Sponsor: Siba Grovogui, associate professor,

Political Science, Krieger School of Arts and Sciences

Daniel Loeser, Baldwin, N.Y.

senior, biomedical engineering

"A Miniaturized Contact Fluorescence Imaging System

Incorporating True Contact and Solid-State

Illumination"

Sponsor: Leslie Tung, associate professor,

Biomedical Engineering, School of Medicine

Holly Martin, Houghton, Mich.

senior, international relations and German

"We Are What We Eat: U.S. Consumption Trends vs.

Sustainable Protein Sources"

Sponsors: Felicity Northcott, lecturer, and Sidney Mintz,

professor emeritus,

Anthropology, Krieger School of Arts and Sciences

Katherine McDonough, Roswell, Ga.

sophomore, history and French

"French Musicians and the Political World of the 1789

Revolution"

Sponsor: Susan Weiss, faculty, Peabody Institute

Paul Nerenberg, Los Angeles

senior, physics

"STILLMix — Surface Tension Impelled Low-Gravity

Liquid Mixing Experiment"

Sponsor: Cila Herman, professor, Mechanical

Engineering, Whiting School of Engineering

Allan Olson, Brattleboro, Vt.

sophomore, civil engineering

"Network Modeling of Polycrystals"

Sponsor: Sanjay Arwade, assistant professor, Civil

Engineering, Whiting School of Engineering

Jin Packard, Baltimore

senior, public health studies

"Mechanism of Vesicular Formation in Yeast Endocytosis"

Sponsor: Beverly Wendland, assistant professor,

Biology, Krieger School of Arts and

Sciences

Scott Pitz, Paoli, Pa.

senior, earth and planetary sciences

"How Do Earthworm Communities Affect the Hydrology of

Agro-Ecosystems?"

Sponsor: Katalin Szlavecz, senior lecturer, Earth

and Planetary Sciences, Krieger School of Arts and

Sciences

Eric Simone, Anderson Township, Ohio

senior, biomedical engineering

"Fabrication of Micro DNA Biosensor Chip with Embedded

Concentration Electrodes"

Sponsor: Jeff Tza-Huei Wang, assistant professor,

Mechanical Engineering, Whiting School of Engineering

Bhuvan Srinivasan, Singapore

senior, biomedical engineering

"Comparison of Deterministic and Stochastic Models of the

PKA Pathway"

Sponsor: Andre Levchenko, assistant professor,

Biomedical Engineering, Whiting School of Engineering

Ankit Tejani, Kingston, Pa.

senior, biomedical engineering

"Use of Erythropoietin as a Novel Treatment in a Murine

Model of Myocardial Infarctions"

Sponsor: Joshua Hare, associate professor,

Biomedical Engineering, Whiting School of Engineering

Denise Terry, Fort Irwin, Calif.

junior, political science

"LIFE: A Photo Essay"

Sponsor: Deborah McGee Mifflin, lecturer, German,

Krieger School of Arts and Sciences

Rebbeca Tesfai, Southfield, Mich.

senior, public health

"The Achievement of Immigrant Populations in Urban High

Schools"

Sponsor: Stephen Plank, assistant professor,

Sociology, Krieger School of Arts and Sciences

Anand Veeravagu, Grapevine, Texas

junior, biomedical engineering

"A Model for the Quantification and Analysis of Long-Range

Spinal Cord Regeneration"

Sponsor: Lawrence Schramm, professor, Biomedical

Engineering, School of Medicine

Simon Zaleski, Ellicott City, Md.

sophomore, piano performance

"Infusing New Beauty into Modern Music Using Ideas From the

Past"

Sponsor: Webb Wiggins, faculty, Peabody Institute

FALL 2002 PROJECTS

Veronica Beaudry, Manchester, N.H.

senior, biology

"F1G1p: A Key Regulator of LACS (Low-Affinity Calcium

Influx System) in Yeast"

Sponsor: Kyle W. Cunningham, associate professor,

Biology, Krieger School of Arts and Sciences

Jeff Chang, San Jose, Calif.

senior, neuroscience

"The Role of IP3 Receptors in Visual Cortical Long-Term

Depression"

Sponsor: Alfred Kirkwood, assistant

professor, Neuroscience, School of

Medicine

Raghu Chivukula, Wichita, Kan.

junior, neuroscience

"Neuroprotective Mechanisms in a Mouse Model of Amyotrophic

Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)"

Sponsor: Katrin I. Andreasson, assistant professor,

Neurology, School of Medicine

David Choi, Fairfax, Va.

senior, psychology

"Stiffness Analysis of an External Fixator System Using

Graphic Modeling and Numerical Simulations"

Sponsor: Edmund Y.S. Chao, professor, Orthopedic

Surgery, School of Medicine

Daniel Davis, Waxhaw, N.C.

senior/master's degree, history; senior, music

composition

"If I Were a Voice, A Historically Based Opera on the

Hutchinson Family"

Sponsor: Michael P. Johnson, professor,

History, Krieger School of Arts and Sciences

Inga Gurevich, Fort Lee, N.J.

senior, neuroscience

"Optimal Parameters for Intrastriatal Transplantation in

Parkinson's Disease"

Sponsor: Anirvan Ghosh, former professor,

Neuroscience, School of Medicine

William Hsu, Westlake Village, Calif.

senior, biomedical engineering

"Modeling High Frequency Membrane Potentials in Cochlear

Outer Hair Cells: Providing Insight Into Active

Hearing"

Sponsor: Alexander Spector, associate

research professor, Biomedical Engineering, Whiting School

of Engineering

Vandna Jerath, Martinez, Ga.

junior, neuroscience

"Autism Netverse: A Literary Journey for the Autistic

Mind"

Sponsor: Tristan Davies, senior

GO TO MARCH 8, 2004

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

GO TO MARCH 8, 2004

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

GO TO THE GAZETTE

FRONT PAGE.

GO TO THE GAZETTE

FRONT PAGE.

|