News Release

|

Office of News and Information Johns Hopkins University 901 South Bond Street, Suite 540 Baltimore, Maryland 21231 Phone: 443-287-9960 | Fax: 443-287-9920 |

June 21, 2005 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Lisa De Nike (443) 287-9960 lde@jhu.edu |

You Can't Pay Full Attention to Sights, Sounds

Lab findings suggest reason cell phones and

driving don't mix

The reason talking on a cell phone makes drivers less safe may be that the brain can't simultaneously give full attention to both the visual task of driving and the auditory task of listening, a study by a Johns Hopkins University psychologist suggests.

The study, published in a recent issue of The Journal of Neuroscience, reinforces earlier behavioral research on the danger of mixing mobile phones and motoring.

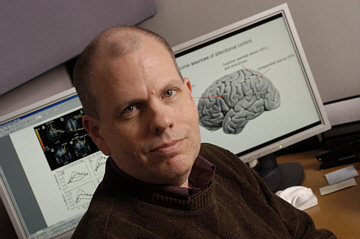

"Our research helps explain why talking on a cell phone can impair driving performance, even when the driver is using a hands-free device," said Steven Yantis, a professor in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences in the university's Zanvyl Krieger School of Arts and Sciences.

|

| Steven Yantis |

"The reason?" he said. "Directing attention to listening effectively 'turns down the volume' on input to the visual parts of the brain. The evidence we have right now strongly suggests that attention is strictly limited — a zero-sum game. When attention is deployed to one modality — say, in this case, talking on a cell phone — it necessarily extracts a cost on another modality — in this case, the visual task of driving."

Yantis's chief collaborator on this research project was Sarah Shomstein, who was a doctoral candidate at Johns Hopkins. Shomstein is now a post-doctoral fellow at Carnegie-Mellon University.

Though the results of Yantis' research can be applied to the real world problem of drivers and their cell phones, that was not directly what the professor and his team studied. Instead, healthy young adults ages 19 to 35 were brought into a neuroimaging lab and asked to view a computer display while listening to voices over headphones. They watched a rapidly changing display of multiple letters and digits, while listening to three voices speaking letters and digits at the same time. The purpose was to simulate the cluttered visual and auditory input people deal with every day.

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), Yantis and his team recorded brain activity during each of these tasks. They found that when the subjects directed their attention to visual tasks, the auditory parts of their brain recorded decreased activity, and vice versa.

Yantis' team also examined the parts of the brain that control shifts of attention. They discovered that when a person was instructed to move his attention from vision to hearing, for instance, the brain's parietal cortex and the prefrontal cortex produced a burst of activity that the researchers interpreted as a signal to initiate the shift of attention. This surprised them, because it has previously been thought that those parts of the brain were involved only in visual functions.

"Ultimately, we want to understand the connection between voluntary acts of the will (for instance, a choice to shift attention from vision to hearing), changes in brain activity (reflecting both the initiation of cognitive control and the effects of that control), and resultant changes in the performance of a task, such as driving," Yantis said. "By advancing our understanding of the connection between mind, brain and behavior, this research may help in the design of complex devices — such as airliner cockpits — and may help in the diagnosis and treatment of neurological disorders such as ADHD or schizophrenia."

This type of work also informs debates about the safety of mobile phone use while driving. It suggests that when attention is focused on listening, vision is affected even at very early stages of visual perception. A paper describing the research appeared in the Nov. 24, 2004, issue of the Journal of Neuroscience (10702-10706).

The National Institute on Drug Abuse funded this research.

To view a short video about this research: www.jhu.edu/news_info/news/audio-video/brain.html.

Color photos of Yantis are available upon request. Contact Lisa De Nike.

|

Johns Hopkins University news releases can be found on the

World Wide Web at

http://www.jhu.edu/news_info/news/ Information on automatic e-mail delivery of science and medical news releases is available at the same address.

|

Go to

Headlines@HopkinsHome Page

Go to

Headlines@HopkinsHome Page