News Release

|

Office of News and Information Johns Hopkins University 901 South Bond Street, Suite 540 Baltimore, Maryland 21231 Phone: 443-287-9960 | Fax: 443-287-9920 |

December 9, 2005 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Lisa De Nike (443) 287-9960 lde@jhu.edu |

Startling Detail

Dark matter in the high-redshift cluster CL 0152-1357. Gravitational lensing analysis with the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) reveals the complicated dark matter distribution (purple) in unprecedented detail when the Universe was at half its present age. The yellowish galaxies are the visible cluster member galaxies forming a filamentary structure, possibly in the process of merging. (Jee et al. 2005, Astrophysical Journal) |

Clues revealed by the recently sharpened view of the Hubble Space Telescope have allowed astronomers to map the location of invisible "dark matter" in unprecedented detail in two very young galaxy clusters.

A Johns Hopkins University-Space Telescope Science Institute team reports its findings in the December issue of Astrophysical Journal. (Other, less-detailed observations appeared in the January 2005 issue of that publication.)

The team's results lend credence to the theory that the galaxies we can see form at the densest regions of "cosmic webs" of invisible dark matter, just as froth gathers on top of ocean waves, said study co-author Myungkook James Jee, assistant research scientist in the Henry A. Rowland Department of Physics and Astronomy in Johns Hopkins' Krieger School of Arts and Sciences.

"Advances in computer technology now allow us to simulate the entire universe and to follow the coalescence of matter into stars, galaxies, clusters of galaxies and enormously long filaments of matter from the first hundred thousand years to the present," Jee said. "However, it is very challenging to verify the simulation results observationally, because dark matter does not emit light."

Jee said the team measured the subtle gravitational "lensing" apparent in Hubble images — that is, the small distortions of galaxies' shapes caused by gravity from unseen dark matter — to produce its detailed dark matter maps. They conducted their observations in two clusters of galaxies that were forming when the universe was about half its present age.

"The images we took show clearly that the cluster galaxies are located at the densest regions of the dark matter haloes, which are rendered in purple in our images," Jee said.

|

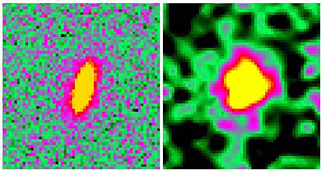

| On the left hand side is an ACS image that shows the lensed galaxy elongated vertically by gravity. However, when the same galaxy is observed with the Very Large Telescope (VLT) at Cerro Paranal, we only see a small blob indicating no hints of lensing (right panel). The shape information has been destroyed by the atmospheric turbulence even if it is much weakerthere than at the sea level. |

The work buttresses the theory that dark matter — which constitutes 90 percent of matter in the universe — and visible matter should coalesce at the same places because gravity pulls them together, Jee said. Concentrations of dark matter should attract visible matter, and as a result, assist in the formation of luminous stars, galaxies and galaxy clusters.

Dark matter presents one of the most puzzling problems in modern cosmology. Invisible, yet undoubtedly there — scientists can measure its effects — its exact characteristics remain elusive. Previous attempts to map dark matter in detail with ground-based telescopes were handicapped by turbulence in the Earth's atmosphere, which blurred the resulting images.

"Observing through the atmosphere is like trying to see the details of a picture at the bottom of a swimming pool full of waves," said Holland Ford, one of the paper's co-authors and a professor of physics and astronomy at Johns Hopkins.

The Johns Hopkins-STScI team was able to overcome the atmospheric obstacle through the use of the space-based Hubble telescope. The installation of the Advanced Camera for Surveys in the Hubble three years ago was an additional boon, increasing the discovery efficiency of the previous HST by a factor of 10.

The team concentrated on two galaxy clusters (each containing more than 400 galaxies) in the southern sky.

"These images were actually intended mainly to study the

galaxies in the clusters, and not the lensing of the

background galaxies," said co-author Richard White, a STScI

astronomer who also is head of the Hubble data archive for

STScI. "But the sharpness and sensitivity of the images

made them ideal for this project. That's the real beauty of

Hubble images: they will be used for years for new

scientific investigations."

Holland Ford, Myungkook James Jee and Richard White |

The result of the team's analysis is a series of vividly detailed, computer-simulated images illustrating the dark matter's location. According to Jee, these images provide researchers with an unprecedented opportunity to infer dark matter's properties.

The clumped structure of dark matter around the cluster galaxies is consistent with the current belief that dark matter particles are "collision-less," Jee said. Unlike normal matter particles, physicists believe, they do not collide and scatter like billiard balls but rather simply pass through each other.

"Collision-less particles do not bombard one another, the way two hydrogen atoms do. If dark matter particles were collisional, we would observe a much smoother distribution of dark matter, without any small-scale clumpy structures," Jee said.

Ford said this study demonstrates that the ACS is uniquely advantageous for gravitational lensing studies and will, over time, substantially enhance understanding of the formation and evolution of the cosmic structure, as well as of dark matter.

"I am enormously gratified that the seven years of hard work by so many talented scientists and engineers to make the Advanced Camera for Surveys is providing all of humanity with deeper images and understandings of the origins of our marvelous universe," said Ford, who is principal investigator for ACS and a leader of the science team.

The ACS science and engineering team is concentrated at the Johns Hopkins University and the Space Telescope Science Institute on the university's Homewood campus in Baltimore. It also includes scientists from other major universities in the United States and Europe. ACS was developed by the team under NASA contract NAS5-32865 and this research was supported by NASA grant NAG5-7697.

High resolution images also are available, as are digital photos of Jee, Ford and White. Contact Lisa De Nike at Lde@jhu.edu.

|

Johns Hopkins University news releases can be found on the

World Wide Web at

http://www.jhu.edu/news_info/news/ Information on automatic e-mail delivery of science and medical news releases is available at the same address.

|

Go to

Headlines@HopkinsHome Page

Go to

Headlines@HopkinsHome Page