|

|

SEPTEMBER 2000 CONTENTS

|

|

HOW WORRIED SHOULD WE BE?

|

|

RELATED SITES

|

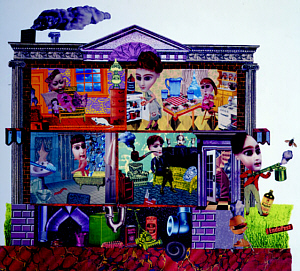

| Plush carpeting. Gleaming cabinets. The savory smell of steaks on the grill. The sweet comforts of home, it seems, may be making us ill. |

Home, Sick Home

By Melissa Hendricks

Illustration by Melissa

Grimes

Here's a hint. Americans spend about 90 percent of their time indoors.

Answer b) is correct for most Americans. Many of the same pollutants spewing out of auto exhaust pipes and smokestacks or languishing in abandoned landfills are also found in the home-- often at levels that would require immediate response if found at a Superfund site.

"The indoor environment is the single most important venue for environmental health," says Timothy Buckley, an assistant professor of environmental health sciences at Hopkins's School of Public Health. "On the order of 75 percent of our risk for carcinogens comes from indoors."

That is true whether you live in industrial Bayonne, New Jersey, or rural Devils Lake, North Dakota, as a long-term study conducted by the Environmental Protection Agency revealed. Starting in 1980, EPA scientists began monitoring the daily exposure of people in several parts of the country to a long list of chemicals. They found that indoor levels of air pollutants surpassed outdoor levels whether the study's volunteers lived in the city, country, or suburbs. Take the volatile organic chemical benzene, for instance. While vehicle exhaust and petroleum and other types of manufacturing produce by far the largest volume of benzene, a person is more likely to encounter a larger dose of the gas indoors, from tobacco smoke, or the off-gassing of paints and adhesives.

The home (or office, school, or car interior), unlike the great outdoors, is a relatively closed environment--a collecting vessel for pollutants generated outside, such as car exhaust, and those used in relatively high concentrations inside, such as air fresheners, mothballs, and cleaning solvents. Various pollutants that collect indoors are associated with health problems, from asthma to cancer, although exactly what levels are harmful is not always clear. Yet environmental laws such as the Clean Air Act, which govern outdoor air quality, stop at the home's doorstep.

The good news: Home dwellers can reduce their risk, through steps as simple as hanging newly drycleaned clothes outside to air out the lingering solvents. Says Buckley, "We have far more control over our indoor environment, which is responsible for most of our exposure."

Radon: The Invisible Threat Downstairs

Radon is an odorless, tasteless, colorless radioactive gas

emitted by uranium-containing soils and rocks such as black

shales, lignite, coal, and some sandstones and granites. It seeps

through cracks in house foundations and sump holes and decays

into charged particles that, when inhaled, stick to the lung's

surface and release alpha particles--potent radiation that can

damage DNA and lay the groundwork for cancer.

Radon is an odorless, tasteless, colorless radioactive gas

emitted by uranium-containing soils and rocks such as black

shales, lignite, coal, and some sandstones and granites. It seeps

through cracks in house foundations and sump holes and decays

into charged particles that, when inhaled, stick to the lung's

surface and release alpha particles--potent radiation that can

damage DNA and lay the groundwork for cancer.

Estimated as the second leading cause of lung cancer, radon contributes to about 12 percent of lung cancer deaths in the United States, says Jonathan Samet, professor and chairman of epidemiology at the School of Public Health, who chaired a National Research Council Committee on the health risks of radon. Most of those deaths are among smokers, although radon is implicated in 19 to 26 percent of lung cancer deaths in non-smokers. These conclusions were drawn in large part by extrapolating from data collected from occupational exposure to radon in miners, who generally inhale larger quantities of radon than are found in most homes. But recent studies on home dwellers are confirming those extrapolations, notes Samet.

While radon is present in all 50 states, the amount varies considerably from home to home, even among houses on the same street, depending on the uranium content of the ground and the porousness and moisture content of the soil, says Samet. Homes in certain regions of the country, such as Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Delaware, tend to have higher levels of radon.

A sure way to reduce the risk posed by radon is to ban smoking in your home. Tobacco smoke and radon appear to raise the risk of lung cancer in a synergistic (i.e., more than additive) fashion.

All homes should be tested for radon, according to the EPA. But be aware that all residences will have a certain background level of radon--not necessarily a cause for concern, unless the level is elevated. Homeowners with radon concentrations 4 picocuries radon per liter of air or higher (affecting perhaps 6 percent of U.S. homes) should attempt to reduce indoor levels. These measures range from opening windows to allow radon to escape, to sealing and caulking cracks in the foundation, to using special venting fans and pipes. Many new homes have radon-resistant construction, such as a four-inch gravel layer covered by plastic sheeting underneath the house.

Samet recommends that homeowners hire only EPA-certified diagnosticians or contractors to perform radon testing and mitigation procedures. For further information about radon, see the EPA's state-by-state listing of contacts: www.epa.gov/iaq/contacts.html.

Formaldehyde: Why Cabinets Can Be Toxic

What do many cabinets, bookcases, floors, cosmetics, food

containers, and textiles have in common? Many brands contain

formaldehyde, a resin that is used as a binder in many types of

pressed wood products such as plywood, wall paneling,

particleboard, and fiberboard. Formaldehyde is a volatile organic

compound; over time, it exits the wood, becoming part of the air

we breathe; it is one of the most ubiquitous indoor air

pollutants.

What do many cabinets, bookcases, floors, cosmetics, food

containers, and textiles have in common? Many brands contain

formaldehyde, a resin that is used as a binder in many types of

pressed wood products such as plywood, wall paneling,

particleboard, and fiberboard. Formaldehyde is a volatile organic

compound; over time, it exits the wood, becoming part of the air

we breathe; it is one of the most ubiquitous indoor air

pollutants.

At high concentrations, this gas is toxic. Lower amounts can cause eye, nose, and throat irritation; wheezing and coughing; fatigue; skin rash; or allergic reactions. Animal studies show high concentrations cause nasal and respiratory cancers; such studies have prompted the EPA to list formaldehyde as a probable human carcinogen.

To reduce risk, experts suggest using hardwood instead of processed wood (an admittedly more costly solution). If you do opt for particle board, choose a brand that is manufactured with phenol-formaldehyde resin, which is less volatile than urea-formaldehyde. Assure proper ventilation.

VOC's: Carpetings Hidden Hazard

Soft, plush carpeting may feel luxurious to your toes, but the

chemicals that carpeting harbors could be hazardous.

Stain-proofing chemicals and the latex backing on many carpets

release volatile organic compounds (VOCs), such as 4-phenyl

cyclohexene, toluene, and styrene. VOCs can cause a variety of

health problems, including eye and respiratory tract irritation,

headaches, and dizziness. Some of these chemicals are suspected

or known carcinogens.

Soft, plush carpeting may feel luxurious to your toes, but the

chemicals that carpeting harbors could be hazardous.

Stain-proofing chemicals and the latex backing on many carpets

release volatile organic compounds (VOCs), such as 4-phenyl

cyclohexene, toluene, and styrene. VOCs can cause a variety of

health problems, including eye and respiratory tract irritation,

headaches, and dizziness. Some of these chemicals are suspected

or known carcinogens.

In addition, carpeting becomes a reservoir for whatever the cat or dog drags in, literally, says Public Health's Buckley, who is studying people's exposure to various air pollutants. Pet dander and urine, dust mites, molds and mildews, even lead and pesticide residues tracked in from outdoors can sink into carpeting, sometimes deeper than a vacuum cleaner can penetrate; the thicker the pile, the greater the reservoir for such contaminants. In one study conducted in the early '90s, researchers from the University of Southern California identified the pesticide DDT in the carpets of 90 of 362 Midwestern homes they examined.

Buckley suggests opting instead for wood floors. If you must use carpet, select one with a lower pile. Vacuum frequently. For installation, choose a water-based adhesive rather than a solvent-based one. Keep windows open and fans running when carpeting is installed, the time when VOCs are highest.

And remember what your mother told you: Wipe your shoes or remove them before you come in!

Chloroform: Shorten Those Shower Songs?

Chloroform may offer one more reason to limit the length of your

showers. This gas forms when chlorine, which is used to disinfect

public water supplies, mixes with organic matter in the water.

The high pressure of showering releases the gas, which the

shower-taker will then inhale. People also absorb chloroform

through their skin and ingest it in drinking water.

Chloroform may offer one more reason to limit the length of your

showers. This gas forms when chlorine, which is used to disinfect

public water supplies, mixes with organic matter in the water.

The high pressure of showering releases the gas, which the

shower-taker will then inhale. People also absorb chloroform

through their skin and ingest it in drinking water.

Chloroform causes kidney and liver tumors in animals, and the EPA lists the chemical as a probable human carcinogen. Rutgers University environmental scientists estimated the increased risk of taking a 10-minute shower every day to be 122 additional cases of cancer per million people--a significant risk.

However, before you give up showering for the rest of your life, consider this. Chloroform is not a typical carcinogen, in which exposure to even a single molecule can set cancer in motion. Instead, evidence indicates that chloroform must reach a certain threshold concentration before it initiates the cancer-causing process, says Buckley. For chloroform to pose any kind of health threat, he says, a person would have to be exposed to this threshhold level of chloroform--a level far higher than is generated during a 10-minute shower.

Those who want to be on the safe side can reduce exposure to chloroform by improving ventilation in the bathroom and drinking bottled water.

ETS: Where There's Smoke, There's Risk

Here is a noxious brew: polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, carbon

monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, hydrogen cyanide, aromatic

hydrocarbons, benzene, formaldehyde, nicotine. Those are a few of

the ingredients in environmental tobacco smoke (ETS)--the smoke

from a smoldering cigarette, pipe, or cigar, plus the

exhalations of a smoker.

Here is a noxious brew: polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, carbon

monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, hydrogen cyanide, aromatic

hydrocarbons, benzene, formaldehyde, nicotine. Those are a few of

the ingredients in environmental tobacco smoke (ETS)--the smoke

from a smoldering cigarette, pipe, or cigar, plus the

exhalations of a smoker.

Exposure can be deadly. Benzene, for example, is a human carcinogen; it is a known cause of leukemia and is associated with several other cancers. Being married to a smoker raises lung cancer risk 25 percent, according to data pooled from several studies. Children of smokers have a greater risk of respiratory infections and slower lung growth. And environmental tobacco smoke is also responsible for an estimated 35,000 to 40,000 cardiovascular disease deaths per year, according to the American Heart Association. ETS may contribute to other cancers too, as well as premature menopause, sudden infant death syndrome, and lower birth weight.

The best way to reduce risk is to avoid smoking. If that is not possible, or if the source of smoke is not you but another member of the household, keep your home as well-ventilated as possible; open windows when the weather permits; and regularly change filters in your heating and cooling system.

Lead: Particle-ly Problematic

Lead may be present in house paint applied as late as 1978, when

the Consumer Product Safety Commission's ban on lead in

residential paint took effect. Older plumbing (pipes, faucets,

soldering) may also contain lead, which can leach into drinking

water. Amendments banning the use of lead in plumbing were added

to the Safe Drinking Water Act in 1986.

Lead may be present in house paint applied as late as 1978, when

the Consumer Product Safety Commission's ban on lead in

residential paint took effect. Older plumbing (pipes, faucets,

soldering) may also contain lead, which can leach into drinking

water. Amendments banning the use of lead in plumbing were added

to the Safe Drinking Water Act in 1986.

Breathing or swallowing lead particles or dust can cause serious neurological impairments, especially in children and fetuses, resulting in delayed physical and mental development, lower IQ and reduced attention span. At high levels, lead can cause convulsions, coma, and death.

"Kids are particularly sensitive because their central nervous systems are developing," says Peter Lees, an associate professor of environmental health sciences at Public Health. Their growing tissues also absorb lead more easily. Parents should be wary of "sources of friction, such as a door that doesn't fit well or windows sliding up and down that can scrape off paint," notes Lees.

All children who live in homes where there might be lead paint should be tested for lead exposure. State health and housing departments can provide information on testing laboratories. Inexpensive home test kits are available, but yield a fair number of false positive results and do not always detect small amounts of lead, says Lees.

An effective, low-cost method of reducing lead indoors is to regularly mop floors, and clean window ledges, and toys with a solution of a phosphate-containing dishwasher detergent. Do not remove, sand, or scrape lead paint yourself, but consult a professional. Never burn wood that has been painted with lead-based paint.

"There are well-established techniques to remove lead paint from houses," says Lees. But professional lead abatement measures can be very expensive, rivaling the cost of the home. An alternative approach is to focus only on key problem areas, for example, replacing lead-contaminated windows and doors, or replacing a deteriorating floor with one that is easier to clean. Lees and Mark Farfel, director of the Johns Hopkins Hospital Lead Poisoning Program, are conducting a study to compare the effectiveness of such lower-budget solutions to full-scale lead abatement.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development provides state-by-state listings of EPA-certified lead evaluators and lead hazard control specialists. Call (888) 532-3547, or see http://www.leadlisting.org. For information on reducing lead in drinking water, contact the National Sanitation Foundation: 877/867-3435, www.nsf.org.

PAHs: Barbecuing Isn't Always Benign

Any type of combustion, particularly inefficient combustion,

produces a host of particles including relatively heavy particles

called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). PAHs have been

shown to cause cancer in animals and are suspected of being human

carcinogens. Exposure may occur through inhalation and

ingestion.

Any type of combustion, particularly inefficient combustion,

produces a host of particles including relatively heavy particles

called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). PAHs have been

shown to cause cancer in animals and are suspected of being human

carcinogens. Exposure may occur through inhalation and

ingestion.

Running a car or lawn mower engine, grilling a steak, and burning a piece of toast generates PAHs. So does cooking in a gunk-encrusted oven or smoking a cigarette. (Combustion also produces potentially harmful gases including carbon monoxide and nitrogen dioxide.)

PAH levels appear to be highest in congested areas, says Timothy Buckley who in a recent study found three times the PAH concentration in urban compared to suburban homes. PAH levels peaked at rush hour.

To reduce exposure, avoid charring food. Toss out that piece of burnt toast. Microwaving does not generate PAHs; boiling produces a minimal amount. Opt for fewer candles, whose burning also generates PAHs. Home air filters (especially a hepa or electrostatic filter) can remove PAHs.

Pesticides: Baits and Traps Beat Sprays

Whether they're out to eradicate ants from the kitchen or rid

Rover of his fleas, most American homeowners use pesticides--a

broad category of chemicals that includes insecticides,

herbicides, and fungicides. Pesticides found in the home include

those applied directly indoors, as well as chemicals applied

outdoors that are tracked in or seep in through cracks and

crevices.

Whether they're out to eradicate ants from the kitchen or rid

Rover of his fleas, most American homeowners use pesticides--a

broad category of chemicals that includes insecticides,

herbicides, and fungicides. Pesticides found in the home include

those applied directly indoors, as well as chemicals applied

outdoors that are tracked in or seep in through cracks and

crevices.

Though large-scale exposure to many pesticides causes immediate symptoms such as headaches, dizziness, and nausea, relatively little is known about the health effects of lower, barely perceptible amounts, says David Jett, a toxicologist at the School of Public Health.

One category of pesticide--the organophosphates--is coming under closer scrutiny because they are now believed to inhibit an enzyme vital to nerve function. In June, the EPA drastically reduced the amount of a common organophosphate called chlorpyrifos in home and garden products, effectively removing the chemical from these products.

Found in dozens of products under the trade name Dursban (or in agricultural products under the name Lorsban), chlorpyrifos is the most common pesticide by volume in the U.S. Studies show it causes brain damage in fetal rats and impairs cognition in adult animals, says Jett. In his own in vitro studies, Jett recently found that chlorpyrifos increases the toxic effects of the polluting PAHs.

Infants and children, whose nervous systems are developing, are most at risk, and certain people may be genetically more susceptible to the damaging effects of organophosphates.

"Be choosy as to which pesticides you buy," advises Jett. Those that contain pyrethroids--synthetic versions of natural pesticides found in chrysanthemums and marigolds--may be safer for home use than organophosphates. The drawback is that pyrethroids do not last as long. "Always follow the manufacturer's recommendations," says Jett. "A lot of the health problems caused by pesticides result from misuse."

To reduce reliance on pesticides, make your house less inviting to pests. Meticulously seal cracks in the floors and walls. Reduce moisture, which attracts carpenter ants and silverfish. Place all food in well-sealed containers or in the refrigerator. Store firewood well away from the home to prevent termite infiltration. Use baits and sticky traps instead of sprays, and search for other alternative methods of pest control.

When spraying pesticides indoors, make sure the room is well-ventilated. Apply flea and tick powders outdoors. And try to apply pesticides only when and where pests are present.

Biological Invaders: Unwelcome Bedfellows

Manufactured chemicals are not the only source of foul indoor

air. Molds, mildew, dust mites, cockroaches, fungal spores,

pollens--all can also inflict serious health problems,

particularly for those prone to asthma and allergies.

Manufactured chemicals are not the only source of foul indoor

air. Molds, mildew, dust mites, cockroaches, fungal spores,

pollens--all can also inflict serious health problems,

particularly for those prone to asthma and allergies.

Molds live in dark, warm, and moist environments such as damp basements, bathrooms, and leaky heating/air-conditioning systems.

"Dust mites tend to feed on dead skin," says John Groopman, chairman of Environmental Health Sciences, and thus are found in bedding, mattresses, upholstery, and carpeting. Researchers now believe that it is principally the feces of dust mites that trigger allergies.

The dander, saliva, and urine of pets also contain allergens, as do cockroaches. And there is some evidence that dust mite or cockroach allergens work in concert with air pollutants such as ozone and particulate matter to exacerbate asthma, says Patrick Breysse, an environmental health scientist at Public Health, who is investigating that theory.

Biological invaders can even occasionally prove fatal. The infamous Legionella bacterium can contaminate building cooling systems, get blown into room air, and become inhaled, leading to the potentially fatal illness known as Legionnaire's disease.

To cut down on dust and allergens in the home, cover mattresses and pillows with impermeable liners and wash bedclothing once a week in water that is at least 140 degrees Fahrenheit. Mop floors and furniture with a damp mop or rag, and vacuum regularly, using a double-layered microfilter bag or HEPA filter. Choose washable curtains or shades.

Keep relative humidity below 50 percent, through use of a dehumidifier or air conditioner, and make sure that air conditioners have proper drainage. Additional tips: add anti-bactericidal solutions to water in humidifiers. Change or clean filters in heating and cooling systems. Install exhaust fans in damp spots like the bathroom and kitchen. Ventilate crawl spaces. In general, any damp, wet, or grungy area is a potential habitat for those creepy, crawly, slimey things of nature and potential ill health.

Melissa Hendricks ( maj@jhu.edu) is the magazines senior science writer.

RETURN TO SEPTEMBER 2000 TABLE OF CONTENTS.